Increasing representation in science seen as important for attracting more Hispanic people to science

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand Hispanic Americans’ perspectives of and experiences with science. We surveyed U.S. adults from Nov. 30 to Dec. 12, 2021, including 3,716 Hispanic adults (inclusive of those who identify as any race). A total of 14,497 U.S. adults completed the survey. A previous report looked at Black Americans’ views and future reports will analyze views among the overall U.S. adult population.

The survey was conducted on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) and included an oversample of Black and Hispanic adults from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel. Respondents on both panels are recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the survey questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

The Center also completed six focus groups with Hispanic Americans from July 13-22, 2021. The focus groups were moderated by Martha Garma Zipper of MGZ Research. Each group discussion was held online for 90 minutes and included three to six men and women; there were a total of 29 participants. Each group was designed to include younger and older age groups, people with higher and lower levels of education, and those living in the metropolitan areas of Chicago, IL; Houston, TX; Phoenix, AZ; and Los Angeles, CA.

Here is the moderator guide used for the focus group discussions, and more on its methodology.

This study was informed by advice from a group of advisers with expertise related to Black and Hispanic Americans’ attitudes and experiences in science, health, STEM education and other areas. Pew Research Center remains solely responsible for all aspects of the research, including any errors associated with its products and findings.

This report is made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which received support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

The terms Hispanic and Latino are used interchangeably in this report.

U.S. Hispanic population, Hispanic population, U.S. Latino population and Latino population refer to all people who self-identify as Hispanic or Latino in the United States, including children and adults. This includes those who say their race is White, Black, Asian or some other race and those who identify as multi-racial. The terms U.S. Hispanic population, Hispanic population, U.S. Latino population and Latino population are used interchangeably in this report.

Hispanic Americans, Hispanic adults, Latinos, Latino adults and Latino people refer to survey respondents who self-identify as Hispanic or Latino in the U.S. This includes those who say their race is White, Black, Asian or some other race and those who identify as multi-racial. The terms Hispanic Americans, Hispanic adults, Latinos Latino adults and Latino people are used interchangeably in this report.

U.S. born refers to persons born in the 50 states or the District of Columbia.

Foreign-born Hispanic Americans refers to persons born outside of the U.S. or born in Puerto Rico. Although individuals born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens by birth, they are grouped with those born in another country for the purposes of this report for a variety of reasons: They are born into a culture that is primarily Spanish-speaking, and on many points their attitudes, views and beliefs are much closer to those of Hispanics born outside the U.S. than of Hispanics born in the 50 states or the District of Columbia, even when compared with those who identify themselves as being of Puerto Rican origin. The terms Hispanic immigrants and foreign-born Hispanic Americans are used interchangeably throughout the report and refer to this group.

Language dominance is a composite measure based on self-described assessments of speaking and reading abilities. Those classified as Spanish-dominant are more proficient in Spanish than in English (i.e., they speak and read Spanish “very well” or “pretty well” but rate their English speaking and reading ability lower). Bilingual refers to people who say they are proficient in both English and Spanish. Those classified as English-dominant are more proficient in English than in Spanish.

Hispanic Americans are one of the fastest growing groups in the nation, a trend that now extends far beyond historic Hispanic population centers to every region and state across the nation. Hispanic Americans are a diverse population, tracing their roots to the island of Puerto Rico, Mexico and more than 20 other nations across Central and South America, with experiences and views about American society often differing widely depending on whether they were born in the United States or immigrated to the country.

A new Pew Research Center survey, accompanied by a series of focus groups, takes an in-depth look at Hispanic Americans’ views and experiences with science spanning interactions with health care providers and STEM schooling, their levels of trust in scientists and medical scientists, and engagement with science-related news and information in daily life

Hispanic adults hold largely trusting views of both medical scientists and scientists to act in the public’s interests. Hispanic adults’ encounters with the health and medical care system are varied, reflecting the diverse nature of the U.S. Hispanic population across characteristics such as nativity, language proficiency, gender, age and education.

Representation is a theme seen across issue areas in the new survey and the data underscores some of the challenges Hispanic adults view – and report experiencing – when it comes to increasing Hispanic representation and engagement with science and allied fields.

Hispanic Americans are glaringly underrepresented among the ranks of scientists and those in allied professions. Hispanic adults make up 17% of the U.S. workforce but just 8% of those working in a science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) job. Since 2010, there has been an increasing share of Hispanic students attending and graduating from college as well as a rise in the share earning a bachelor’s degree in a STEM field. Even so, Hispanic students remain underrepresented among college graduates and among master’s and doctoral degree-earners in STEM.

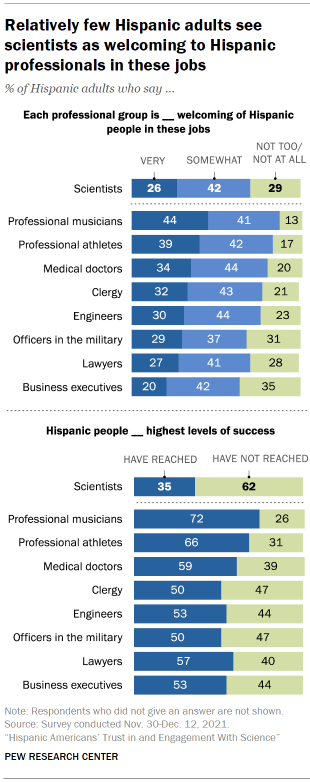

The survey findings suggest that most Latinos see scientific professions as potentially “unwelcoming” to Latino people. For example, just 26% of Latinos feel that scientists as a professional group are very welcoming of Latinos in these jobs; another 42% say they are somewhat welcoming. About three-in-ten (29%) view scientists as not too or not at all welcoming of Latinos in their ranks.

Perceptions of medical doctors’ openness toward Latino colleagues are slightly better: roughly a third describe medical doctors as very welcoming of Latinos in these jobs (34%). While scientists are not the only professional group that Latinos view as less than very welcoming, perceptions of scientists are among the lowest measured across the nine groups included in the survey.

Hispanic adults also express a sense that Hispanic people are not visible at the highest levels of success in science careers. About six-in-ten say that Hispanic people have not reached the highest levels of success as scientists; fewer (35%) believe that they have.

Perceptions of Hispanic achievement as engineers and medical doctors are relatively more positive: 53% and 59%, respectively, think Hispanic people have reached the highest levels of success in these professions.

One focus group participant put the connection between representation and trust this way:

“I think we need to know more Latino scientists. I think … well, actually, I don’t know any Latino scientists that I would say, “Oh yes. That’s that scientist … So maybe if we knew some scientists that made a discovery that was Latino we would trust science more.” – Latina, age 25-39

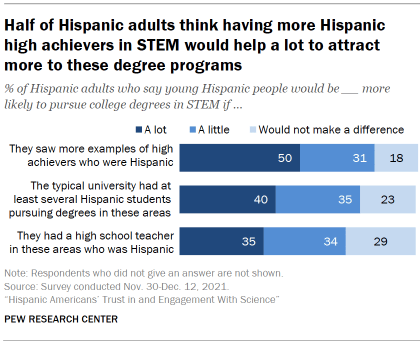

The survey highlights greater visible achievement among Hispanic Americans as a potential driver of STEM engagement among Hispanic Americans, including the pursuit of college degrees in these fields.

A large majority of Hispanic adults say that seeing more examples of high achievers in STEM who are Hispanic would help a lot (50%) or a little (31%) to encourage more young Hispanic people to pursue college degrees in STEM fields.

Majorities also say young Hispanic people would be at least a little more likely to pursue college degrees in STEM if the typical university had at least several Hispanic students in STEM degree programs and if Hispanic students had a high school STEM teacher who was Hispanic.

A sizable share of Hispanic college students are the first in their immediate family to attend college. The survey finds first-generation Hispanic college students are especially likely to view representation in the form of more examples of high-achieving Hispanic people in STEM as a catalyst for greater engagement: 60% think this would make young Hispanic people a lot more likely to pursue STEM degree programs.

When thinking about ways to increase engagement with science among Hispanic Americans, focus group participants frequently raised the issue of representation.

“More of us. We need to see more of our people.” – Latino, age 25-39

“Just that, incorporate more Latino people in it, starting with school, involve kids in technology and science, and develop more projects about strategies, those type of things, for the kids to get more interested and see it more like a game and therefore begin to have a love for science.” – Latina, age 40-65

Past experiences with STEM schooling can play a pivotal role in whether or not people engage with science or pursue further training or a job in STEM. The survey paints a mixed picture when it comes to Latinos’ past experiences in the classroom.

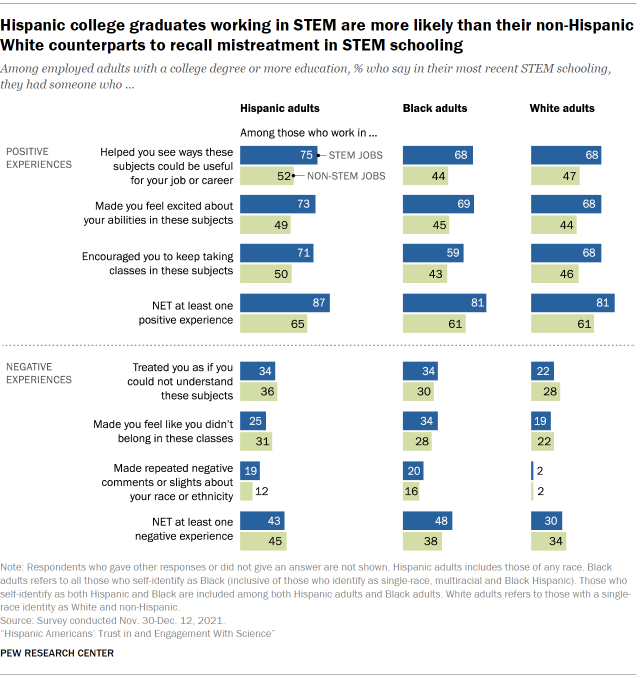

Most Hispanic college graduates working in STEM fields can recall positive experiences from their most recent educational experiences in science, technology, engineering and math – such as someone who encouraged them to keep taking classes in these subjects.

However, Hispanic college graduates working in STEM jobs are significantly more likely than non-Hispanic White college graduates in these positions to say they faced mistreatment in their most recent STEM schooling. For instance, 34% say they can recall someone treating them as if they could not understand the subject matter – significantly higher than the share of non-Hispanic White adults working in STEM who say this (22%).

In all, 43% of college-educated Hispanic STEM workers say they had at least one of the three negative experiences asked about in the survey. The experiences of Hispanic college graduates in this regard are similar to those of Black college graduates, who are also far more likely than non-Hispanic White college graduates to recall any of these three negative experiences in their STEM schooling.

The survey, conducted Nov. 30 to Dec. 12, 2021, includes 3,716 Hispanic adults; findings based on all Hispanic adults surveyed have a margin of error of plus or minus 2.6 percentage points.

The questions asked in the survey were informed by a set of six focus groups among Hispanic adults, conducted virtually in July 2021, that elicited views about the COVID-19 pandemic, experiences and beliefs about the health and medical care systems, as well as people’s interests in science topics and their thoughts about ways to increase trust and engagement with science in Hispanic communities. The study also drew guidance from a panel of advisers with expertise on Hispanic and Black Americans’ views and experiences in American society broadly and in connection with science, health and STEM education.

A common theme recurring in both focus group discussions and conversations with the expert advisory panel was how the diversity of the U.S. Hispanic population is central to experiences with science across all aspects of society.

The survey data reveal these differences by characteristics such as nativity and language proficiency across science topics, but they appear especially central to Hispanic Americans’ interactions with and views about medical care.

For instance, while the share of Latinos with health insurance is up over the last decade, Latino immigrants remain less likely than those born in the U.S. to have health insurance. Latino immigrants (especially those who have been in the country for 20 years or less) also are less likely than other Latinos to say they have seen a health care provider in the past year or that they have a primary care provider who they usually turn to when they are sick or need health care.

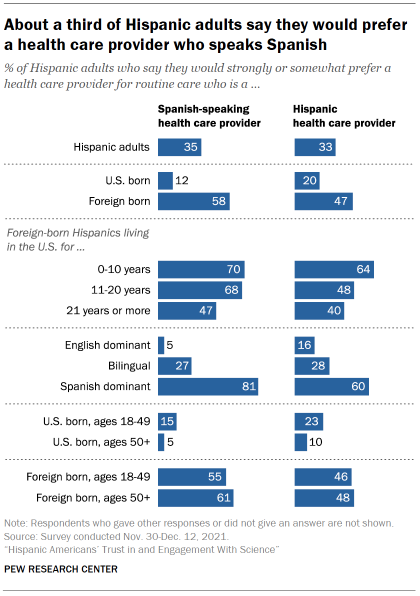

The interconnected characteristics of nativity and language proficiency are major factors shaping preferences in seeking out health care. Foreign-born Hispanic adults – a group that is much more likely to be Spanish-language dominant – are far more likely than those born in the U.S. to say they prefer to see a Spanish-speaking health care provider (58% t0 12%) and to prefer a Hispanic provider (47% to 20%).

Underscoring issues of representation in the medical profession, just 7% of all physicians and surgeons are Hispanic, according to a Center analysis of federal government data, far lower than the share of Hispanics in the overall workforce.

When it comes to negative experiences with health care, 52% of Latino adults say they’ve had at least one of six negative experiences with health care providers in the past – such as having to speak up to get the proper care. In this, experiences of Latino adults are more similar than different to those of all U.S. adults.

However, the relatively small share of Hispanic Americans who identify their race as Black (3%) are much more likely than Hispanic Americans who identify as White or as some other race to report negative health care interactions. A large majority of Black Hispanic adults (69%) say they’ve faced one of six negative experiences with health care providers, such as feeling that the pain they were experiencing was not being taken seriously. By contrast, a smaller share of White Hispanic adults (50%) say they’ve had one of these six negative experiences with doctors or other health care providers.

Trust in medical scientists and engagement with COVID-19 news and information

The coronavirus pandemic and the development of COVID-19 vaccines has put renewed focus on public levels of trust in medical scientists and scientists, especially in the Hispanic population that has faced disparate health impacts from COVID-19.

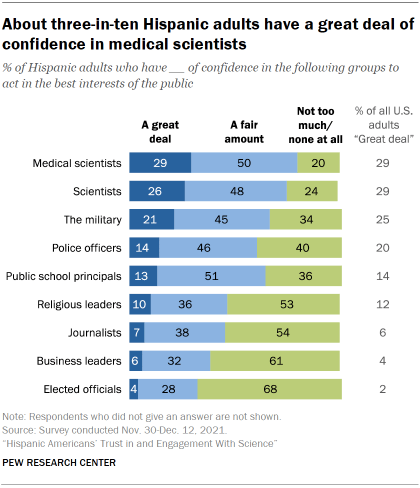

Hispanic adults hold largely trusting views of both medical scientists and scientists to act in the public’s interests. About three-in-ten Hispanic adults (29%) hold a strong level of trust in medical scientists, saying they have a great deal of confidence in them to act in the public’s best interests. Half say they have a fair amount of confidence in medical scientists, while 20% express more negative views, saying they have not too much or no confidence in medical scientists.

Trust in scientists is similarly positive. A large majority of Hispanic Americans have either a great deal (26%) or a fair amount (48%) of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests. (Half of the survey respondents were asked for their views of medical scientists and half were asked for their views of scientists, generally.)

Hispanic Americans’ trust in medical scientists and scientists is higher than it is for other groups and institutions, including the military, police officers and K-12 public school principals.

Still, as with the general population, Hispanic Americans’ confidence in medical scientists is down from earlier in the coronavirus pandemic. In April 2020, 45% of Hispanic adults had a great deal of confidence in medical scientists. That figure was 30% in November 2020 and is roughly the same (29%) in the current survey. Similarly, confidence in scientists has also fallen since the early stages of the coronavirus outbreak.

As with views of scientists in the general population, Hispanic adults with a college degree or more education are generally more trusting of medical scientists and scientists than those with less education. Hispanic Democrats tend to hold more trusting views of these groups than do Hispanic Republicans – in line with partisanship patterns seen among all U.S. adults.

Hispanic Americans’ broadly positive views of scientists are consistent with the reliance they report on experts to make sense of news about the coronavirus and COVID-19 vaccines.

Hispanic adults express broad engagement with coronavirus news and information; the survey was fielded in December 2021, amid a surge of coronavirus cases stemming from the omicron variant. About half of Hispanic adults (47%) say they talked about coronavirus-related news nearly every day or a few times a week. Among social media users, 73% of Hispanics report having seen coronavirus content in the past few weeks. These levels of engagement with coronavirus news and information among Hispanic adults are similar to those seen among all U.S. adults.

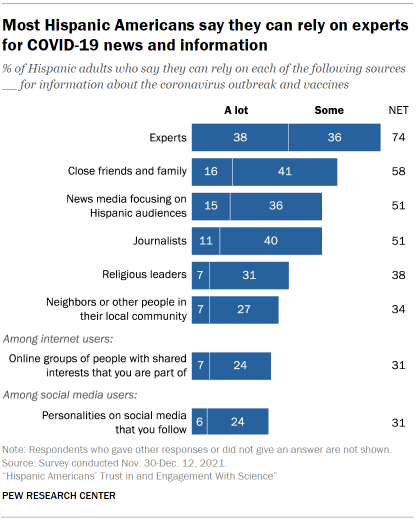

Changes to public health guidance and information about the coronavirus outbreak and vaccines have proven confusing to many Americans. When asked about potential sources of coronavirus information, Hispanic Americans are more likely to say they can rely on information from experts than any of seven other sources considered in the survey.

Roughly three-quarters of Hispanic adults (74%) say they can rely on information from experts in this area either a lot or some; 21% say they can rely on experts not too much or at all.

Close friends and family also play a prominent role when it comes to information about the COVID-19 outbreak and vaccines: 58% of Latinos say they can rely on close friends and family a lot or some.

About half of Latinos say the same about information on this topic from journalists and from news media focused on Latino audiences. Smaller shares say they can rely on other sources for information about the coronavirus outbreak and vaccines, including religious leaders and neighbors.