Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, May 24. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Newsletter

Get our free Coronavirus Today newsletter

Sign up for the latest news, best stories and what they mean for you, plus answers to your questions.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It’s been well over a year since doses of COVID-19 vaccines started going into Americans’ arms. Nearly 585 million doses have been administered in the U.S. alone, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and two-thirds of the population is considered fully vaccinated. Serious side effects are extremely rare — affecting roughly 10 people per 1 million doses given — and there have been nine deaths. The fatalities were among those who’d received the Johnson & Johnson shot, which officials now view as a backup. The vaccines also have prevented more than 2.2 million deaths through the end of March, the Commonwealth Fund estimates.

That’s an impressive track record. Yet roughly 1 in 6 American adults still insist they’re just fine without a COVID-19 vaccine and have no plan to get one. The Kaiser Family Foundation’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor found that 17% of those surveyed last month said they would “definitely not” get vaccinated. That’s the highest figure the tracker has recorded to date; a year ago, 13% of adults surveyed gave the shots a hard no.

The newfangled vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna induce human cells to make a key piece of the coronavirus spike protein by following a blueprint encoded in messenger RNA. Those manufactured proteins then train the immune system to recognize — and hopefully neutralize — the real viral threat.

The reasons for skepticism about the shots run the gamut. Some worry they’ll cause side effects that won’t reveal themselves for years. Others fear they’ll interfere with their fertility (although the evidence to date is reassuring on that front).

Then there are more outlandish concerns, such as that the vaccines will alter their DNA (an impossibility, since they don’t enter the cell nucleus where DNA resides) or implant a microchip so the government (or Bill Gates) can track their movements (a thoroughly debunked conspiracy theory).

Can an old-school vaccine persuade these holdouts to roll up their sleeves at last?

The folks at Novavax sure hope so. Their COVID-19 vaccine works the old-fashioned way, delivering an exact replica of the spike protein into the bloodstream so the immune system can scope out its enemy in advance. It’s the same approach used to immunize people against shingles and flu.

Some people “may prefer tried and true technologies” for COVID-19 vaccines, Dr. Filip Dubovsky, the chief medical officer of Novavax, told my colleague Melissa Healy. Though he described himself as a fan of the mRNA vaccines, he said others “may not like the concept of … turning their body into a little vaccine factory.”

He and his colleagues are hopeful that the company’s product, known as NVX-CoV2373, will appeal to some of the millions of still-unvaccinated Americans, as well as those who are reluctant to get an mRNA booster shot.

Dr. Gregory Poland, a vaccine expert at the Mayo Clinic who has consulted with Novavax and other companies, stated things a little more bluntly: “This would not be a ‘genetic vaccine.’ And people wary of ‘genetic vaccines’ might find it more appealing.”

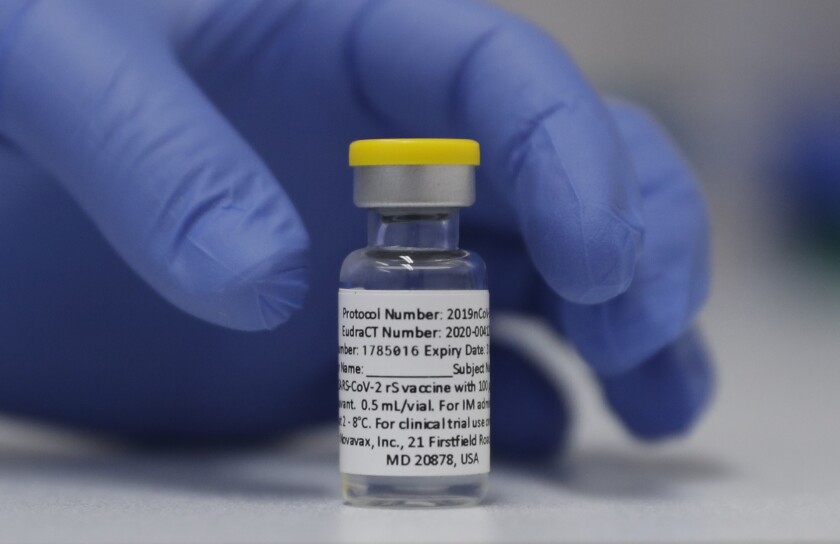

A vial of the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine is ready for use in a Phase 3 clinical trial in London.

(Alastair Grant / Associated Press)

There are other selling points too.

Those opposed to abortion may appreciate that, unlike the mRNA vaccines, the one from Novavax wasn’t developed with cell lines created from fetal tissue. Younger men and others concerned about the risk of myocarditis, a rare but potentially serious type of heart inflammation associated with mRNA vaccines, may see NVX-CoV2373 as a safer alternative. And those who spent a day laid up in bed after getting a dose of Comirnaty or SpikeVax may try to avoid a repeat by giving the Novavax shot a try.

And then there are the practical considerations, including the fact that it doesn’t need to be kept chilled to ultra-cold temperatures. Nor does it need to be reconstituted by people with special skills.

There is one significant drawback, for now at least: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not yet authorized it for emergency use.

The reason for the holdup is unclear. The World Health Organization endorsed it in December, and regulators in 28 countries — where the shot is known as Covavax or Nuvaxovid — have given it a green light as well. Novavax said it intended to produce 2 billion doses of the vaccine this year.

“This is a very good vaccine, but the FDA has slow-walked it every step of the way,” said Lawrence Gostin, an expert in public health law expert at Georgetown University.

The agency’s vaccine advisory panel is scheduled to discuss NVX-CoV2373 at its meeting on June 7. Panel members will consider clinical trial data that showed the vaccine was 100% effective in preventing mild and moderate cases of COVID-19 among 30,000 adults in the U.S. and Mexico at a time when the original coronavirus strain was still dominant. In another trial of U.S. and Mexican adolescents, the vaccine was 80% effective in preventing COVID-19 when the more formidable Delta variant was dominant. Side effects — mainly pain at the injection site, headaches and fatigue — were mild and infrequent.

How the vaccine will fare against Omicron and its subvariants is likely to be a big topic of discussion. Novavax’s Dubovsky said the fact that the vaccine had had a steady rate or efficacy across a range of variants was a promising sign that it would hold its own not only against Omicron but also future variants that are bound to arise.

Gostin noted that an endorsement from U.S. regulators might slow the emergence of new variants by persuading more people around the world to be vaccinated. The more people who are protected, the fewer hosts the coronavirus will find — and the fewer opportunities it will have to mutate.

“Having the FDA authorize it in the United States would boost confidence in this vaccine globally,” he said.

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:40 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Is it curtains for live theater?

Go to the beach, visit a mall, or try to get somewhere during rush hour and you may come away convinced that life in Los Angeles is pretty much back to a pre-pandemic normal. But step into one of the city’s live theaters and you’ll see that the performing arts still have a long way to go.

Audience attendance this spring is roughly half what it was before the coronavirus came along and darkened stages for well over a year. Operating capacity is down by a similar amount, according to a recent survey organized by local arts organizations.

Even more ominous: Ticket revenue is only one-third of what it used to be while COVID safety measures — including the installation of pricey air filtration systems and the hiring of a dedicated monitor — make productions more expensive. And that’s without taking higher rents and inflation into account.

Initially, many arts organizations were able to remain afloat thanks to government pandemic grants and loans, as well as financial support from concerned donors. That money is no longer available.

“There’s a foreseeable financial cliff ahead of us,” Gustavo Herrera, executive director of Arts for L.A., told my colleague Jessica Gelt. “And I think that’s what we’re really concerned about.”

It’s not hard to see why. A report from McKinsey & Co., the management consulting firm, suggests it could take more than five years for the arts sector to match its 2019 contribution to the national economy.

Even Broadway is struggling. So many shows had their openings delayed either by Omicron or its subvariants that the Tony Awards extended the eligibility period by six days to make sure voters had a chance to see everything, Variety reported. Lackluster ticket sales left at least 25% of seats empty in the last week of April, according to Forbes.

The interior of the Pasadena Playhouse during a rehearsal of Holland Taylor’s show “Ann.”

(Mariah Tauger / Los Angeles Times)

It’s not that no one is going to the theater. But those who are see fewer shows, and when audiences are pickier, it’s “hard to stage riskier plays or challenging material — or to do new work or introduce new artists,” said Snehal Desai, producing artistic director of East West Players.

Even the venerable Center Theatre Group is grappling with the unpredictable circumstances. It opened “A Christmas Carol” at the Ahmanson Theatre on Nov. 30 — its first show in nearly two years — but had to close the production in mid-December after Omicron infiltrated the cast. That resulted in a $1.5-million loss. Then in February, CTG staged “Slave Play” at the Mark Taper Forum and set a box-office record for a five-week engagement.

Thor Steingraber, executive and artistic director of the Soraya at Cal State Northridge, said some theatergoers were put off by the inconsistent rules about masks and vaccines.

When the L.A. County Department of Public Health required proof of vaccination along with an indoor mask mandate, both venues and patrons knew what to expect, he said. Now that each theater can set its own rules, things feel arbitrary and patrons are anxious and irritable. Some have reacted angrily when asked to mask up, complaining that they didn’t have to in other venues.

“Whatever we do, it has to inspire consumer confidence,” Steingraber said. “And if consistency is the thing that inspires consumer confidence, then I’m all for it.”

He’d probably get an endorsement from those who lost their jobs and are eager to get back to work. The National Endowment for the Arts says more than half a million jobs disappeared from the arts economy during the first year of the pandemic. Unemployment in the arts spiked to 30%, according to SMU DataArts, with BIPOC and disabled workers disproportionately affected.

Wren T. Brown is the producing artistic director and co-founder of Ebony Repertory Theatre in Mid-City, where audiences are “really thin.” But he has an idea for turning things around.

“There has to be a real narrative about the vital importance of the arts in troubled times, like that of the pandemic,” Brown told Gelt. “There is something profound about the communal dynamic of performing arts, and if we start focusing on what we do, and why it’s meaningful and impactful on society, I think we will go a long way toward encouraging a quiet return to the theater.”

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

In other news …

Is California in for another bummer summer? With the number of coronavirus cases climbing fast, it’s a possibility the state can’t afford to ignore.

As of Friday, California was reporting 231 new cases per 100,000 residents per week. That’s a 63% increase over the previous week and a level not seen since the winter’s Omicron surge. Anything above 100 new cases per 100,000 people per week is considered a “high” rate of transmission by the CDC.

Weekly coronavirus cases more than doubled in Riverside County (from 81 to 163 new cases per 100,000 residents) and in Santa Barbara County (from 107 to 228 new cases per 100,000 residents). Case rates also increased 87% in Orange County (to 171 per 100,000), 85% in San Bernardino County (to 147 per 100,000) and 84% in Ventura County (to 201 per 100,000).

Los Angeles County saw more modest growth — 31% week over week — but its rate of 266 new cases per 100,000 residents per week is higher.

Southern California is faring better than the Bay Area, where the case rate jumped 78% to 369 new cases per 100,000 residents per week. Case rates are highest along the San Francisco Peninsula: 410 per 100,000 per week in Santa Clara County, 412 per 100,000 per week in San Mateo County, and 460 per 100,000 per week in San Francisco, which now claims the highest case rate among California’s 58 counties.

That may come as a surprise considering the Bay Area has generally fared better than Southern California. In part, that’s due to the region’s intensive efforts to keep the virus under control. But that success may become a liability because so many residents have not been exposed to the virus until now, experts said.

Dr. Robert Kosnik, director of UC San Francisco’s occupational health program, predicts cases will keep climbing for at least the next couple of weeks: “I know that’s not good news, but that’s kind of what the data is pointing to.”

UCSF has responded by implementing a universal masking policy at all events with at least 100 attendees. Across the bay in Berkeley, the school system reinstated its indoor mask mandate for students and staff. Cases are so widespread that schools can find substitutes for only about half of the teachers who are calling in sick.

Weekly cases have roughly doubled in the Greater Sacramento region (now at 213 per 100,000 residents) and the San Joaquin Valley (now at 139 per 100,000). And they’re up 83% in rural Northern California (which also has 139 cases per 100,000 per week).

The good news is that hospitalization rates remain low for now despite rising for the last four weeks. The California Department of Public Health said the growth in COVID-19 hospitalizations had been slower than in past surges.

A bummer summer might turn out to be the least of our concerns if Congress doesn’t allocate more funds to fight COVID-19, according to Dr. Ashish Jha, the White House coronavirus response coordinator. He and his colleagues in the Biden administration are making plans to ration supplies of vaccines and medications in case Congress doesn’t come through with the money.

Federal officials have been warning for weeks that nearly all of the $1.9 trillion in the American Rescue Plan earmarked for the pandemic response has been spent. Figuring out what to do with the small amount that remains involves making tough choices, like whether to buy more of the drugs that dramatically reduce the risk of severe illness or invest in next-generation vaccines.

Having to let any of these necessities go would mean ceding some of the advances made against the coronavirus over the last two years, Jha has warned in public and private meetings. If orders for tests, vaccines and treatments aren’t placed in the coming weeks, other countries might buy up all available supplies and leave the U.S. empty-handed, he said.

Speaking of COVID-19 treatments, doctors and public health officials are trying to understand why some people who take the drug Paxlovid to clear their coronavirus infections are becoming sick again after completing their treatment.

The phenomenon is known as “post-Paxlovid rebound.” It’s unclear how often it happens, but the fact that it happens at all means that people should be cautious if they develop COVID symptoms after taking the drug.

“It can happen,” said Dr. Robert Wachter of UCSF, who knows of at least one such case. “If you develop recurrent symptoms and have a [positive] rapid test, you are infectious. Please act accordingly.”

Jha said researchers were trying to figure out whether instances of post-Paxlovid relapses were rising because more people were taking Paxlovid or because the drug’s efficacy was waning as new Omicron subvariants spread.

The U.S Food and Drug Administration said it was aware of reports of post-Paxlovid relapses. In a clinical trial for the drug, about 1% to 2% of patients tested negative for coronavirus infections and then tested positive — but this happened to people who got Paxlovid and to people who took the placebo.

Moving on to vaccines, the CDC has recommended COVID-19 booster shots for school-age children if it’s been at least five months since they finished their primary series. Offering a third dose to 5- to 11-year-olds should shore up their protection as coronavirus cases rise, officials said.

The FDA authorized the kid-sized booster from Pfizer and BioNTech early last week, but it took a couple of more days for the CDC to consult with its vaccine advisory panel and then make a decision.

As for children under 5, Pfizer and BioNTech said Monday that three shots of the super-low-dose version of their vaccine were 80% effective at preventing COVID-19 symptoms. They added that the three-shot regimen produced enough virus-fighting antibodies to meet the FDA’s criteria for emergency use authorization, and that no safety problems were seen.

The findings are still preliminary, and the study volunteers are still being tracked. The companies will need to see at least 21 cases of COVID-19 to make a final determination of the vaccine’s effectiveness; so far there are 10. Pfizer and BioNTech tested a three-shot series of Comirnaty after a clinical trial of two doses produced disappointing results among preschoolers. The dose for children ages 6 months to 4 years is one-tenth the dose for adults.

Some health experts are saying the adult version of Comirnaty could have prevented China’s costly coronavirus outbreak that resulted in disruptive lockdowns in Shanghai, Beijing and other cities.

Studies have consistently shown that the Pfizer vaccine and its counterpart from Moderna offer the best protection against severe and fatal cases of COVID-19. A Chinese drug company made a deal back in the spring of 2020 to distribute Comirnaty, and eventually manufacture it. Officials in Hong Kong and Macao have authorized the vaccine. But the Chinese government hasn’t cleared it for use on the mainland — a decision some see as putting politics and pride above public health.

Regulators haven’t gone public with an explanation for the delay. But sources with knowledge of the matter told the Associated Press that China wanted to master mRNA vaccine technology on its own so it wouldn’t be dependent on foreign suppliers.

And finally, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus was reelected Tuesday to a second term as director-general of the World Health Organization. Despite criticism over the WHO’s response to the pandemic (or perhaps because of them), Tedros ran unopposed.

The vote came during the 75th World Health Assembly in Geneva. In opening the meeting Sunday, Tedros warned that the pandemic was “most certainly not over.”

Nearly 1 billion people in lower-income countries have yet to be vaccinated, and cases are on the rise in almost 70 countries around the globe, he said. Meanwhile, the decline in testing and sequencing is handicapping our ability to respond to the ever-evolving coronavirus.

“We lower our guard at our peril,” he said.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How many Americans who died of COVID-19 were unvaccinated?

This question was prompted by last week’s news that the U.S. had recorded its 1 millionth COVID-19 death. (As of Tuesday afternoon, the tally is 1,002,711, according to the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard.)

I’m going to edit this question before I answer it. Pretty much all of the 350,831 Americans who died of COVID-19 in 2020 became infected before they had the opportunity to be vaccinated, and combining their deaths with those of people who died after passing up the chance to be immunized makes it hard to see the difference vaccines make. The same goes for unvaccinated people who died in 2021 when the shots were still being rationed.

The better question is this: How do COVID-19 death rates for unvaccinated Americans compare with those for vaccinated Americans?

The answer is, they’re consistently higher for people who aren’t vaccinated, though the size of the gap has changed over the last year or so.

The CDC reports that on April 10, 2021 — when the most vulnerable Americans and front-line workers had been offered the shots but some younger and healthier adults were still waiting their turn — there were 2.83 COVID-19 deaths for every 100,000 unvaccinated Americans, compared with 0.14 for every 100,000 fully vaccinated Americans. That means the risk of death was about 20 times higher for those who were unvaccinated.

Both rates have tended to rise and fall in tandem since then. On Aug. 21, 2021, when the Delta variant was on the rise, the mortality rate for unvaccinated Americans rose to 17.95 COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 people. That same day, there were 1.16 COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 vaccinated people.

The next peak came on Jan. 15 of this year. On that day at the height of the Omicron surge, there were 24.14 COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 unvaccinated Americans, compared with 2.47 per 100,000 vaccinated Americans.

Among Americans 5 and up — that is, those who are old enough to get a vaccine — the risk of dying of COVID-19 in March was 10 times higher for unvaccinated folks than for vaccinated ones, the CDC says.

The gap is more pronounced when you add booster shots to the mix. Among Americans 12 and up — that is, those old enough to qualify for a booster — the risk of dying of COVID-19 in March was 17 times higher for unvaccinated Americans than for those who were vaccinated and boosted, according to the CDC.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

(Richard Drew / Associated Press)

The critter in the photo above is a rat, and he’s standing on a subway platform in New York City’s Times Square. Sightings like this are more common than they’ve been in a decade, and experts say the pandemic is probably to blame.

In the first four months of this year, New Yorkers reported roughly 7,400 rat sightings to the city’s 311 line. That’s up more than 60% compared with a similar period in 2019, the last full year before the pandemic.

A little perspective: In all of 2010 (the earliest year for which online records are available), the city received about 10,500 rat reports. 2022 is on track to pass that soon, especially considering that rats are most visible when it’s warm.

The spike in sightings doesn’t necessarily mean the rat population has grown. Perhaps they’re just more visible now, lured into the open by the proliferation of outdoor seating at restaurants.

NYC Mayor Eric Adams hopes to cut the rodents off from their food supply by replacing overflowing trash bins with padlocked models. Animal rights activists are sure to see that as an improvement over his 2019 endorsement of foul-smelling traps in which rats drown to death.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.