Jose’s journey across the desert from Mexico was a dangerous one. During the night, a rattlesnake bit one of his party of migrants, and the group’s guide — their coyote — forced them to leave her in the desert to die.

Another migrant died in Jose’s arms after he was bitten by a spider. When Border Patrol agents descended upon the group inside the United States, Jose and the others scattered into the desert.

Jose finally found his way to Vermont.

Juana also walked across the desert, where she was forced to drink water from puddles, filtering it through her shirt to avoid ingesting insects. Her first job in the United States was at a Sonic Burger in South Carolina. Later she worked in the tobacco fields of Kentucky. By then she was pregnant, and her aunt had told her there were better jobs in Vermont.

Now she and her husband live on a Vermont dairy farm, where he works 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Juana is pleased that in Vermont they are able to get medical care for their children, and she has found companionship with other women as part of a gardening project. Their oldest son has joined them, but their daughter is still in Mexico.

Juana says, “My heart will be forever split between two places.”

Carlos has worked on a number of farms in Vermont, losing jobs sometimes because of his drinking problem. He is able to send money back home, but he is sad that he missed his daughter’s 15th birthday celebration, and he misses the music he and his family used to play together.

Alcoholism is a disease, he says. It feeds on loneliness. There is plenty of work in Vermont, he says, but he hopes his children don’t have to come here like he did.

For most Vermonters, the state’s migrant farmworkers are an invisible population. There are between 1,000 and 1,200 of them, and the state’s dairy industry depends on them. But they live mostly in seclusion, reluctant to let themselves come to the notice of immigration authorities or police.

Because of their isolation, they are often invisible to each other, as well.

That’s why Julia Doucet, an outreach nurse for the Open Door Clinic in Middlebury, decided to help them share their stories with fellow migrants. Mental health problems caused by isolation and cultural dislocation had become a cause for concern, so she collected their stories, told in Spanish, in pamphlets for distribution among the workers.

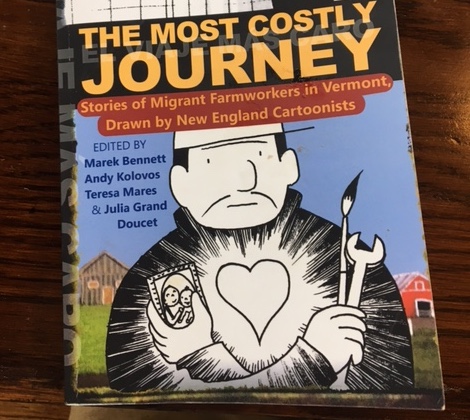

Now Vermont’s invisible population is becoming more visible. The Vermont Folklife Center, in collaboration with a number of other organizations, has published 19 of those stories, translated into English, in a book called “The Most Costly Journey.” The stories are told in the words of the workers themselves, incorporated into comics by some of the region’s most accomplished cartoon artists.

The Vermont Reads selection for 2022

“The Most Costly Journey” promises to become a major cultural event in Vermont. In part, that’s because the Vermont Humanities Council has chosen the book as its Vermont Reads selection for 2022. That means libraries, schools, book clubs, government agencies and others throughout the state will take up the book as a focus for reading and discussion.

Vermont Humanities has 3,500 copies for distribution to readers.

In a foreword to “The Most Costly Journey,” author Julia Alvarez writes: “Deep within the migrant community exists its own powerful resource: storytelling. A story can cross any boundary, including the often mostly heavily guarded boundary, between self and other, us and them. It is portable, easy to carry across deserts and oceans, languages and cultures.”

Alvarez, who came to the United States from the Dominican Republic, is full of appreciation for the migrant community. “Who else would milk our cows, grow our food, process it, cook and serve it? Who would feed and bathe our viejitos in nursing homes and hospitals, look after ninitos in day care centers and preschools?” She says, “We need narratives to help us navigate our way home to the circle of our shared humanity.”

Two of the editors of “The Most Costly Journey” emphasize in an afterword that the workers were consulted at every step as their stories were put into book form. The editors mean to assure readers no cultural appropriation was involved in creation of the book.

The words of the migrants are stark and truthful, and the artists’ illustrations underscore their power. The storytellers are protected by the use of pseudonyms, but the authenticity of their stories is evident.

Each migrant traveled a different route to Vermont. Alejandro was born in Georgia, so he is a U.S. citizen, but he is living with his father, Felix, working in Vermont and dreaming of the day both can go back home to Chiapas state.

Jesus fled the robberies, kidnapping and extortion caused by the gangs of Veracruz. The demands for money didn’t end even after he came to Vermont, and he thanks God for the strength to carry on.

Each has his or her own struggle

A common theme among the storytellers is how much they miss home — parents, brothers, sisters. Many have spent years in Vermont, but they are living apart from their families because they want to help them, sending money back home that will allow parents to buy a house or otherwise improve their lot.

The sacrifice and commitment of the workers echo stories told of migrants of the past who endured hardship and loneliness after arriving from Italy or Ireland, Poland or Greece.

Each individual has his or her own struggle. Jose expresses pride in the work he is doing on the farm in Vermont, but he speaks about how much he misses home. Then one day he is gone, and the editors of the book are unable to finish the story. No one knows where he went.

Other migrants talk about the importance of learning English, of obtaining a driver’s license, or working hard and learning how to do the work on the farm. A farmer named Bob, who has hired a worker named Carlos, says, “I have a tremendous amount of respect for these guys from Mexico. They go through hell to get here and it’s all for their families. These guys are willing to work — they want to work! Don’t assume that they’re stupid or below you because they don’t speak the same language.”

Vermont is not on the front line of immigration from Mexico, but immigration isn’t new to the state. Previous generations have experienced the arrival of earlier waves of immigrants, and today those earlier immigrants, along with the Native Americans who were here first, constitute what Vermont is. It is impossible to conceive of Vermont without an appreciation of the mixture of peoples who have formed the state.

The journalist and historian Howard French, who has written about the central role of Africa and Africans in the formation of what we call the New World, has described the importance of “Creole” culture wherever diverse cultures come together. By that, he means more than the blend of Black and white commonly known as Creole in New Orleans or the Caribbean. He means the vibrant blend of people open to the other — a jazz orchestra or a fiesta of Mexican music and cuisine.

In fact, hundreds have turned out in Middlebury and elsewhere to consume the food of immigrant cooks. Organizations have sprung up to drive farmworkers to appointments and to see to their medical needs. The waiting room of the Open Door Clinic, which serves those without insurance, is a lively bilingual setting, Creole in the best sense meant by Howard French.

‘How comics can be used’

In creating the new book, important Vermont institutions have rallied around the cause of the state’s migrant population. The project began with the Open Door Clinic and enjoyed the help of Teresa Mares, an anthropologist at the University of Vermont. Mares brought in the Vermont Folklife Center and Andy Kolovos, a folklorist and archivist at the center.

Kolovos described himself as “an old-school comic book nerd” and friend of Marek Bennett, one of the cartoonists who have added a whole new dimension to the migrants’ stories. As a folklorist, Kolovos said he was interested in “exploring how comics can be used to tell ethnographic stories.” In fact, comics are popular in Mexico, and the farmworkers were happy to participate in the graphic depiction of their stories.

Now Vermont Humanities is bringing these stories to all of Vermont. For a period several years ago, I was a member of the board of Vermont Humanities and am aware of its mission to bring the humanities to the community.

In making “The Most Costly Journey” its Vermont Reads selection, Vermont Humanities is enlarging the community by embracing some of its newest members.

Graphic novels and cartoon art are evolving as a serious form of storytelling, and as an expression of the humanities — and of our common humanity — “The Most Costly Journey” is an important contribution.

Did you know VTDigger is a nonprofit?

Our journalism is made possible by member donations. If you value what we do, please contribute and help keep this vital resource accessible to all.