Project overview

This study was carried out from August 2020 to January 2021, with focus groups conducted from November to December 2020. We used principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR), an approach that draws on the strengths of diverse partners, shares resources, and fosters shared decision making and knowledge creation [26]. Aligning with this approach, we convened a community advisory board of 10 members with representation from healthcare systems, healthcare providers, growers, community health workers, and medical and premedical students that met monthly to oversee the project, facilitate relationship building, and offer advice. The leadership team also met regularly with partnering public health officials and healthcare leaders to discuss COVID-19 testing service delivery (e.g., location of testing sites, hours of operation) and the engagement of more vulnerable communities in testing services.

The larger project included three aims: 1) support the delivery of COVID-19 testing services, 2) broadly disseminate COVID-19 public health information, and 3) conduct research on perceptions of the coronavirus and COVID-19 testing and vaccination among Latinx/Indigenous Mexicans in rural agricultural communities in Inland Southern California. As reported elsewhere, the larger project was successful in carrying out Aims 1 and 2 of the study [27]. The team’s leadership established access to routine COVID-19 testing for rural, immigrant communities partnering with a federally qualified health center and county public health to conduct 26 testing clinics providing approximately 1470 tests. Additionally, community health workers or promotores de salud disseminated COVID-19 related public health information via social media, at COVID-19 testing events, and in-person socially distanced community talks. These efforts resulted in 22 virtual COVID-19 community talks (Pláticas de COVID-19) livestreamed on our Facebook page @Unidoporsalud and 10 in-person COVID-19 community talks (Pláticas en el Pueblo).

For the purposes of this article, we focus on the findings from our third aim involving research on the coronavirus and COVID-19 perceptions. Prior to the start of data collection, we obtained ethical approval for the study from the University of California Riverside’s Institutional Review Board.

Study setting

Our study focused on the effects of the coronavirus pandemic amongst Latinx and Indigenous Mexican immigrant communities in the rural desert region of Inland Southern California. Our research was carried out in Riverside County, an area of California in which racial-ethnic minority populations have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. At the time of the study, Riverside County had the second highest number of confirmed cases and deaths in the state [28, 29]. There are over 2 million Latinos in Riverside County, a majority minority population that outnumbers all other racial and ethnic groups in the region [30,31,32]. Most Latinos are of Mexican origin, with smaller numbers of Puerto Ricans, Salvadorans, and Guatemalans, and Indigenous Nations [33]. Latinos in this region suffer health disparities due to low income and education, limited English proficiency, and undocumented status [34,35,36]. Unsurprisingly, the pandemic has severely impacted this population in the region: At research inception in fall 2020, which aligned with wave two spread of the coronavirus in California, county level data indicated the Latinx population accounted for 57% of COVID-19 cases and 46% of deaths in Riverside County [28, 29, 37, 38].

Our study focused on engaging Latinx and Indigenous Mexicans in rural agricultural communities in the eastern part of the Coachella Valley in Riverside County. The Coachella Valley, a 45-mile-long valley encompassing nine cities and rural agricultural communities, is an area of particular racial-ethnic disparity. This area is home to several vulnerable communities including the unincorporated rural communities of the Eastern Coachella Valley (ECV): Mecca, North Shore, Oasis, and Thermal, home to many Latinx and Indigenous Mexican immigrants living below the poverty line and working in the nearby agricultural fields. This region is home to the Purépecha community, an Indigenous Mexican population from the state of Michoacán [34]. At the start of the pandemic this region was identified as a hotspot, with some reports indicating a COVID-19 infection rate in the ECV 5 times higher than other Coachella Valley communities [39].

During the time of our study, these unincorporated rural communities (Mecca, North Shore, Oasis, and Thermal) consistently reported the highest rates of COVID-19 cases per 1,000 residents in the Coachella Valley. For instance, in September 2020 Thermal reported > 130 cases/1,000 residents, which increased to > 250 cases/1,000 residents in January 2021. This is significantly higher than case rates in Palm Springs (also in the Coachella Valley), which reported > 20 cases/1,000 residents in September 2020 and > 50 cases/1,000 residents in January 2021 [40].

This pattern of increased total confirmed cases of COVID-19 in these ECV communities continued throughout the study period. In September 2020, Mecca had 455 cases increasing to 1079 cases in January 2021; North Shore had 136 cases increasing to 331 cases; Oasis had 333 cases increasing to 826 cases; and Thermal had 185 cases increasing to 440 cases [40]. An increase in deaths due to COVID-19 accompanied the increased cases. In September 2020, Mecca had 9 reported deaths increasing to 16 in January 2021; North Shore had 1 reported death and remained stable; Oasis had 5 reported deaths increasing slightly to 6; and Thermal had 0 reported deaths increasing to 4 deaths [40].

Ethnographic observations

During community advisory board meetings, meetings with partners (e.g., public health, healthcare leaders), and attendance at meetings with growers we made ethnographic observations and jotted down key discussion topics [41]. Team members reflected on these observations and used this information to inform the focus group interview guide and analysis and interpretation of the data.

Focus group eligibility and recruitment

Promotores de salud recruited community members into the focus groups by distributing study flyers with eligibility criteria and study contact information to individuals and families in their social networks. Eligibility criteria were met if a community member: 1) was 18 years of age or older, 2) lived in the ECV and/or farm-working community along the Salton Sea, 3) self-identified as Latino/Hispanic, Latinx and/or indigenous from Latin America, and 4) spoke Spanish and/or Purépecha. Monolingual English-speaking Latinos and monolingual speakers of an indigenous dialect other than Purépecha were excluded from participation.

Data collection

A focus group is a group interview that allows qualitative researchers to gather collective data about a specific phenomenon of interest. This method of data collection allows participants to build on each other’s ideas [42], providing collective (rather than individual) knowledge about the structural and socio-cultural factors shaping perceptions of the coronavirus and attitudes and behaviors around COVID-19 testing and vaccination. From November to December 2020, we conducted seven virtual focus groups (of six to ten people each) to elicit information on shared structural stressors and socio-cultural factors shaping attitudes and behaviors around COVID-19 testing and vaccination. For nonprobability samples, 80% of themes can be identified within two to three focus groups and 90% within three to six focus groups [43].

Promotores de salud facilitated the focus groups with assistance from medical and pre-medical students. All facilitators received training on qualitative data collection and data analysis. Facilitators used a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions to elicit information on shared beliefs and attitudes around the virus, its spread, and COVID-19 testing and future vaccination, as well as risk-reduction behaviors such as social distancing and use of face coverings. We prompted discussion about themes emerging from our ethnographic observations and conversations with community members during public health outreach and testing events, including trust in public health officials, the government, and providers/healthcare systems, as well as strategies and tools to support those with COVID-19 and increase risk-reduction behaviors and use of COVID-19 testing services. At the end of all focus groups, participants were asked to complete a socio-demographic survey, either by using a link to a Qualtrics (online) version of the survey, or by having a team member administer the survey to them via phone.

Data analysis

Focus groups were conducted via Zoom video conference, audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using template and matrix analysis, a rapid qualitative analytic technique [44,45,46]. This technique involved summarizing all focus group transcripts using a template organized by the key topics of the semi-structured interview guide (template analysis). Key domains included: coronavirus, its spread, and ways to reduce virus propagation; attitudes and beliefs about COVID-19 testing, barriers to testing, and resources for people testing positive; and thoughts about COVID-19 vaccines and barriers to vaccination. A matrix was then created to organize the responses from each summary template (as rows) by key domains (as columns). Promotores de salud and students participated in a 2-part training on template and matrix analysis and led data analysis with support from experts in this analytic approach. Team members read transcripts line-by-line and inserted data, including illustrative excerpts from the interviews, in the templates. Next, a matrix (focus group × domain) was created, and data from each template were inserted into the matrix. The matrix facilitated the identification of cross-case themes/patterns across the seven focus groups conducted.

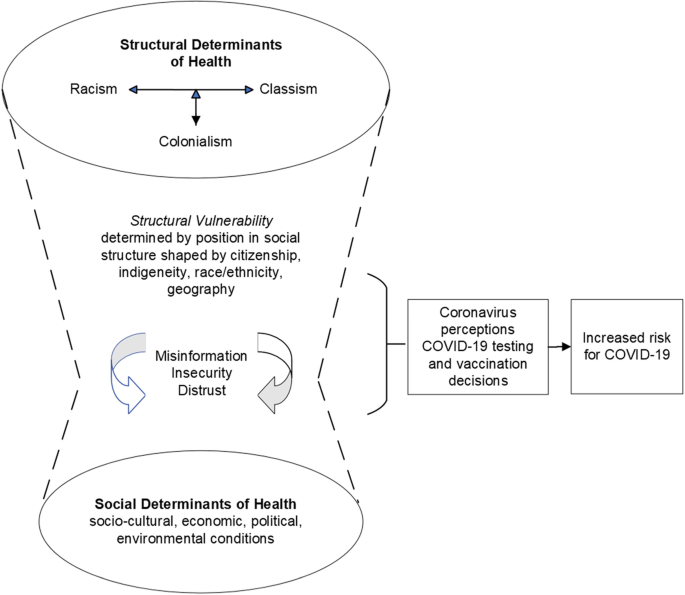

Through this iterative process of theme identification and constant comparison across cases, we developed a conceptual model (Fig. 1) grounded in the data that reflects the relationships among themes and their connection with COVID-19 testing and vaccination. We used exemplar quotes to substantiate these patterns. Participant quotes were translated from Spanish to English by the first author, a native English speaker proficient in Spanish. Graduate and PhD-level bilingual (Spanish–English) team members then checked participants quotes for accuracy and validated them.