As the Russian invasion of Ukraine escalates against the backdrop of the pandemic, new sanctions on the Russian investment fund that owns the COVID-19 vaccine Sputnik V, plus broader bans on financial transactions with Russia, present vaccine manufacturers and countries in the Global South with a new dilemma.

On 28 February, the US Department of Treasury announced sanctions on several Russian state-owned organizations, expressly naming the sovereign wealth fund Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) and describing its CEO Kirill Dmitriev as a “known Putin ally”. As per the announcement, “[Putin and] his inner circle of cronies have long relied on RDIF and Dmitriev to raise funds abroad, including in the United States”. Similarly, the EU will apply sanctions from March 12 prohibiting European involvement in projects financed by RDIF. More broadly, US and EU sanctions prohibit transactions with Russia’s central bank.

RDIF has retaliated with a response insinuating these restrictions were a result of lobbying efforts by Western pharma companies and the fund itself “was never involved with any political activities, [and] does not interact in any way with Ukraine”.

RDIF is the financial backer of Sputnik V and its one-shot cousin Sputnik Light, designed by Moscow’s Gamaleya Federal Research Center of Epidemiology and Microbiology. Manufacturers contracted to produce these vaccines now face an uncertain evolving scenario wherein financial, reputational, and supply chain considerations will drive major decisions.

Meanwhile, many countries in the Global South are waiting for the delivery of Sputnik doses to support their immunization programs. The vaccine is approved in major economies including Russia, India, and Mexico. Additionally, a subsidiary of RDIF had signed a long-term agreement with UNICEF to supply several countries including Zambia, Yemen, Uganda, Somalia, Paraguay, and Nigeria with doses for 110 million people. This supply was pending Sputnik’s Emergency Use Listing from the World Health Organization (WHO).

But that approval now seems unlikely: Gamaleya submitted its application to the WHO in December and January and was expecting a manufacturing inspection in Russia in February from the WHO. There have been no updates on the approval process, a UNICEF spokesperson told GlobalData PharmSource; Emergency Use Listing by the WHO is a prerequisite for the procurement of any vaccine candidates, and the Sputnik vaccine has not been approved by WHO for Emergency Use. An EMA approval for Sputnik V has long been delayed.

Sputnik V manufacturing plans stall

While details on the exact way in which the imposed sanctions may affect Sputnik V contracts are scant, restrictions by the international community on Russia’s use of the SWIFT financial network mean it’s hard to see how foreign governments and NGOs could pay Russia for the doses. Vaccine prices are generally given in dollars and RDIF may try to renegotiate some of these contracts in another currency, but the only other currency that could probably be used is Chinese yuan, says Paul Stronski, senior fellow, Russia and Eurasia program, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. But China is a competitor itself, with the CoronaVac vaccine produced by Sinovac Biotech, Convidecia by CanSino Biologics, BBIBP-CorV produced by Sinopharm Group, and other homegrown vaccines, so the sanctions have added another layer of complexity to doing financial transactions with RDIF, says Stronski. As per some sources, India is exploring rupee trade accounts in response to Western sanctions.

Before the outbreak of war, manufacturing organizations from across the world signed contracts to produce Sputnik V. Indian contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) top this list, with eight entities including major pharma players like Serum Institute of India, Morepen Laboratories, and Hetero Drugs. Serum Institute alone is contracted to supply 300 million doses of Sputnik, and Virchow and Stelis are contracted for 200 million doses each. Even though India’s sanctions against Russia do not including banking or pharmaceuticals to date, sanctions by other countries could affect contracts and supply chains. Other contract manufacturing deals have been made in China (including with Hualan Biological Engineering for 100 million doses) and with CMOs IN Vietnam, Turkey, Egypt, and South and Central America.

Soon after the Russian invasion, the president of Bavaria announced that the German state would no longer allow Sputnik V to be produced at a facility in the region. The region had signed a letter of intent in April 2021 with RDIF to purchase 2.5 million vaccine doses upon EMA authorization. The Russian pharma company R-Pharm had set up a production facility in Illertissen, Bavaria, to produce the vaccine. Even if Sputnik were to be approved by the EMA – now a more unlikely prospect than ever – “it is inconceivable from our point of view that this project can now be realized. It is over,” Bavaria’s president told the state’s parliament.

Figure 1: Manufacturing facilities contracted to produce Sputnik

Source: GlobalData Pharmaceutical Intelligence Database, accessed March 4, 2022 © GlobalData

Notes: Sputnik V and Sputnik Light doses

Experts say CDMOs outside Russia might be able to continue to manufacture the vaccine if they have already obtained the necessary IP from Gamaleya and if they do not require unique raw ingredients from the institute. If the complete technology transfer between a manufacturing unit and Gamaleya is assumed, CDMOs could probably manufacture the vaccine in a fully independent fashion, says Vasily Medvedev, Head of Development at viral vector CMO Exothera. But if a Russian entity holds the license, it will likely need to be involved in the final lot release process and it’s not clear how the current crisis or sanctions would impact regulatory authority engagement, says Chris Murphy, vice president and general manager, Viral Vector Services at ThermoFisher Scientific.

Some Sputnik manufacturing contracts are with Russian CDMOs, intended for the domestic market and export to some countries like Iran. This production will remain in Russia but it is complicated to get goods in and out of Russia, as certain countries have banned Russian airlines from their airspace, Stronski says. In addition to that, goods transported via the Black Sea or railways have also been obstructed. However, barriers against Russian technology transfers for vaccines out of the country may be less fiercely enforced than for other imports because of the humanitarian need, Stronski says. Furthermore, Russian supply is limited: in 2021 Russia turned to Chinese CMOs to manufacture more Sputnik doses for the Russian market – a move that the Kremlin claimed was because popular demand exceeded supply, but may have been caused by reported domestic manufacturing problems.

A pivot to other vaccines?

If producing Sputnik outside Russia becomes impossible, CDMOs might achieve a pivot to other COVID-19 vaccines to fill the shortfall in doses for the Global South. It is more likely that they would switch to one of the similarly formulated recombinant virus vaccines, or the even cheaper-to-make inactivated or subunit vaccines on the market than an mRNA vaccine, which requires niche machinery that comes with a very high upfront cost.

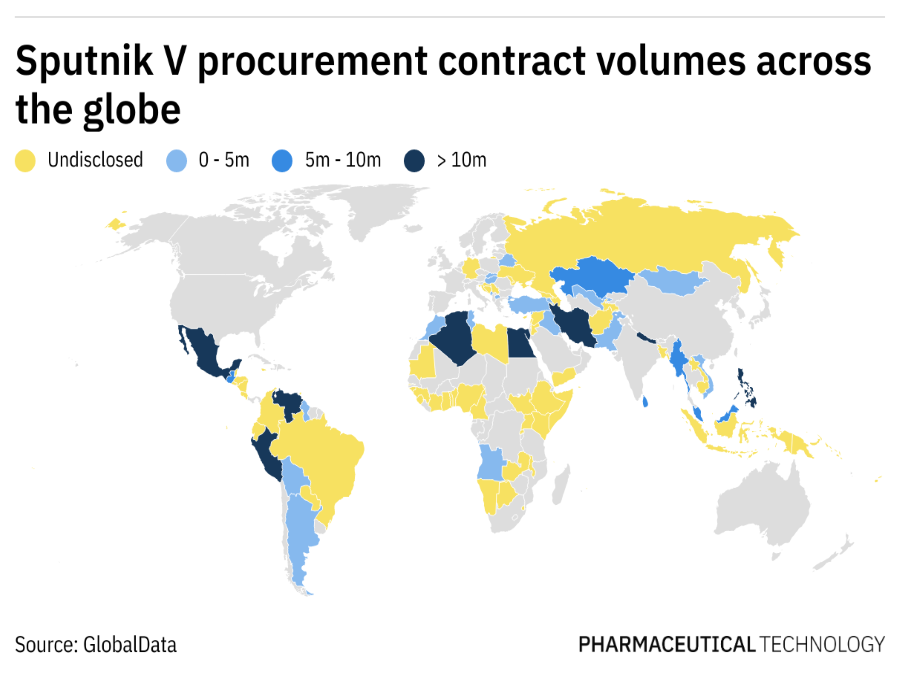

Figure 2: Sputnik V procurement contracts, by doses ordered

Source: GlobalData Pharmaceutical Intelligence Database, accessed March 7, 2022 © GlobalData

Notes: Contracts signed by governments or procurement facilities such as COVAX

Minimum order volumes displayed; some countries have both a governmental contract and access to a second source of doses through COVAX

Sputnik V is a two-dose vaccine made of two adenovirus vectors, recombinant adenovirus type 6 and 5 (rAd26 and rAd5), while Sputnik Light – marketed as a standalone one-shot vaccine – is just the first rAd26 component. The first shot is engineered to express SARS-CoV-2 proteins to “prime” the immune response, and the second to express SARS-CoV-2 proteins and “boost” the response. While viral vector manufacturing is complex, over the last two years, manufacturers have built on existing expertise to fast-track the production of adenoviral vector vaccines for COVID-19. Other adenovirus vaccines on the market for COVID-19 are the Johnson and Johnson one-shot vaccine, which relies on the rAd6 vector, like Sputnik V; the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine uses chimpanzee adenovirus (ChAdOx1) vector. Chinese company CanSino is also marketing an adenovirus vaccine based on Ad5, Convidecia, in China, Indonesia, and Mexico.

As per news reports, supply delays in producing the second shot with rAd5 pushed the introduction of Sputnik Light. Because of its production characteristics, rAd6 grows very well and can be made and purified cheaply, says adenovirus researcher EJ Kremer, Université de Montpellier, France.

Companies are likely to already have the base assets, processing space, and analytics to transition to a different version of adenoviral vector, says Murphy. It would be reasonably straightforward to adapt the manufacturing capacities of such CDMOs to the other targets, if the process “philosophy” and key steps are preserved, says Medvedev. Still, Murphy says it could take close to 9–12 months for a CDMO to make the transition and then produce and release the new viral vector product, particularly if there are specific materials that need to be procured that are in high demand. Even before the pandemic, viral vector manufacturing capacity was in shortage worldwide.

Beyond the viral vector problem, the finished dose manufacturing is likely to be the rate-limiting step versus the active pharmaceutical ingredient, Murphy says.

Sputnik’s checkered history

Even before the most recent events in Ukraine, Sputnik V supply has sputtered with a series of setbacks, with countries like Guatemala complaining about low supplies, accompanied by a dipping interest in taking the vaccine. Indian manufacturers have found it difficult to find takers for their existing stock. Even in Russia, the birthplace of Sputnik V, vaccination rates remain relatively low, with less than half of the country’s population being fully vaccinated.

Stronski brought up another factor that may influence what happens next: the reputational risk that companies face by continuing to engage with Russian entities like RDIF in producing the vaccine. “There’s a whole slew of global companies who’ve decided that it’s not worth their business [with Russia],” he says. There will likely be even more pressure on countries like Serbia or others that aspire to join the EU or are allied with the United States, he adds. The war does not find support even in countries like India, which haven’t officially broken off with Russia, given the continuing crisis involving thousands of Indian students trapped in the country, says Stronski.

Many governments in Latin America are already looking elsewhere to secure vaccines for the future, says Beatriz Garcia Nice, program coordinator, Latin American program, Wilson Center. This is not only because of the war between Russia and Ukraine, but because now more than ever, the WHO is very unlikely to grant the Sputnik V vaccine recognition, she adds. Some countries with existing contracts for Sputnik V, like Argentina, Uruguay, and Mexico, have also approved other COVID-19 vaccines. When safety concerns regarding Sputnik V were raised, Kremer says many people wanted to choose other vaccines based on their individual designs or safety profiles, but a lot of people just don’t have that option.

Graphs by data journalist Ovanes Penchev