It’s been 35 years since Patricia “Patsy” Whitefoot’s youngest sister, Daisy Heath, disappeared from the home they shared in rural eastern Washington. The unsolved case has shaped the lives of Whitefoot and her family as they continuously cycle through waves of yearning, anger and grief. A detective called just a couple of months ago with a lead that ultimately, like all the others, went nowhere.

But while the decades haven’t produced any answers about Heath’s whereabouts, they have brought definitive change — in attitudes, awareness and technology, which are now offering new hope for Whitefoot and dozens of other families in the Yakima Valley suffering similar agony.

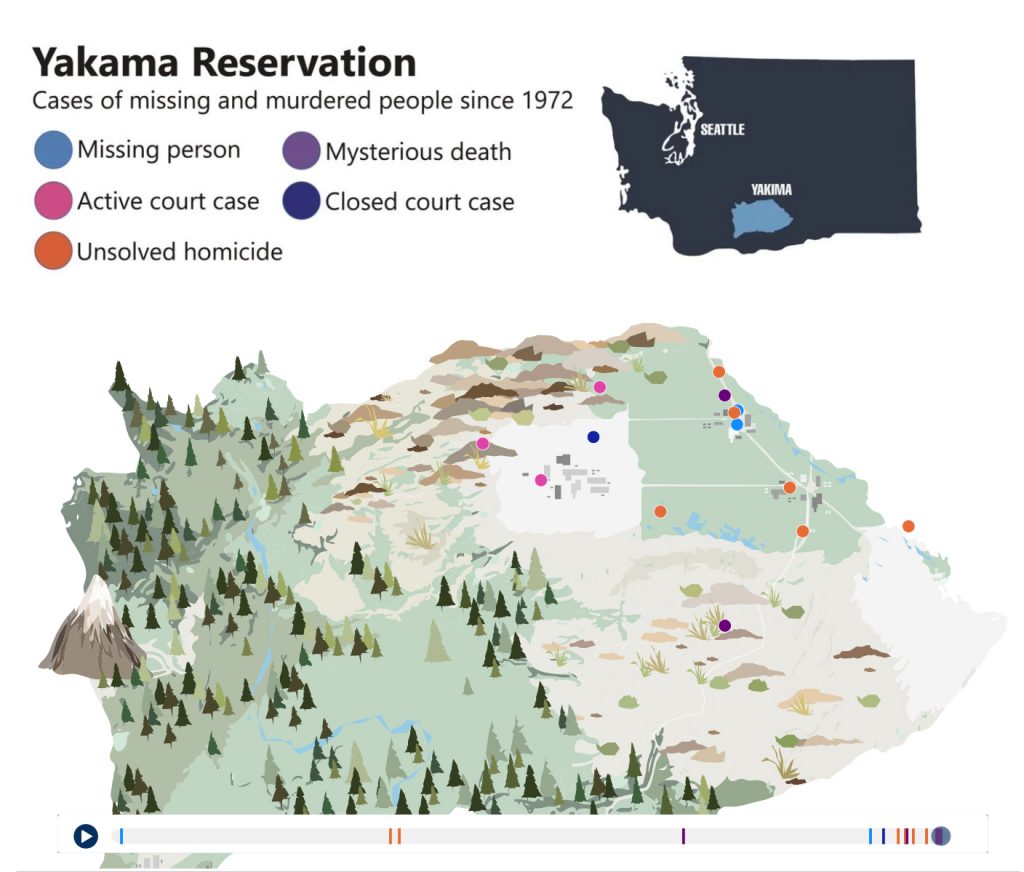

The local newspaper is taking advantage of that new technology for a project called “The Vanished,” a unique repository of stories and information about dozens of missing and murdered Indigenous women from the area, with an interactive map and timeline that highlight the massive scale of the situation while narrowing in on each life. The project has raised awareness, brought the community together and spurred new legislation and a state task force.

“It’s always my hope that maybe the right person sees the map and says, ‘I remember this,’” says reporter Tammy Ayer. “And that could maybe solve the mystery for a family that’s been wondering for decades. These people aren’t statistics. Their stories need to be told.”

Ayer and her colleagues at the Yakima Herald-Republic are swimming against multiple tides.

Heath is one of at least 28 missing Indigenous people with ties to the Yakama Nation or the area around the reservation, according to a lengthy Washington State Patrol list of unsolved disappearances that was created last year, and the state of Washington has one of the highest numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in the U.S., according to the Urban Indian Health Institute. The nationwide crisis has gone largely under the radar due in part to cultural divides, stereotypes, jurisdictional complexities, systemic bias and geographic barriers.

The Herald-Republic’s editors recognized the need for more coverage and scrutiny of the issue, yet the paper’s newsroom has shrunk by almost half over the past decade as the struggling journalism industry has seen more than 2,100 local newspapers in the U.S. go under since 2004, including 16 in Washington. News organizations in rural communities like Yakima have been hit the hardest, especially as the pandemic further decimated advertising income from local businesses, which were shuttered during lockdowns.

The small newspaper’s efforts are getting a boost from Microsoft, a founding supporter of a philanthropic initiative to support democracy by preserving local journalism. Through a partnership with the Yakima Valley Community Foundation, the tech company and local groups are contributing funding, technology tools such as Power BI data visualization software, training and more to the Herald-Republic, its Spanish-language sister paper, and local radio and TV stations.

In the summer of 1987, Heath was living with Whitefoot in the shadow of the Cascade Mountains near the town of White Swan, about an hour’s drive down the valley from the city of Yakima, helping care for Whitefoot’s three school-aged children. The athletic 29-year-old would come and go from their home, Whitefoot says, which wasn’t unusual for their family.

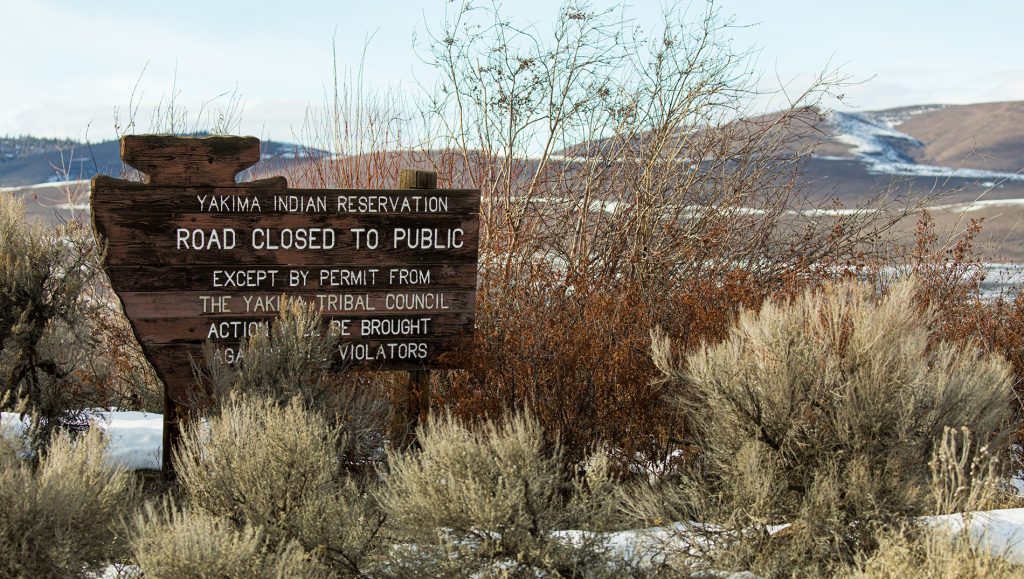

The Yakama – whose tribal name has a different spelling than the city or valley – were traditionally a migratory people, moving with the seasons around the valley and beyond to hunt, fish and harvest traditional foods such as huckleberries. Whitefoot’s family members often follow those ancient practices, sometimes camping in the mountains until it starts getting cold in September or October, and sometimes visiting relatives on other reservations around the Pacific Northwest.

So Whitefoot didn’t think much of Heath’s absence until another sister called one day and said it was time to start asking around. Family members throughout the region began spreading the word and checking popular gathering sites along the Columbia River.

It didn’t hit home that Heath was truly missing until a detective from the Bureau of Indian Affairs showed up. As the realization flooded over her, Whitefoot says she became angered by the detective’s questions and then, after he left, fell into a deep, unresponsive depression for days.

Whitefoot had had little interaction with law enforcement or the news media. Both were viewed with suspicion in the community. But as the reality of her sister’s disappearance set in, she found herself slowly becoming a public force of advocacy and education, recently even hosting the War Cry podcast with three other Indigenous women, about missing and slain women in the Pacific Northwest.

“I began to learn more about all these women in the community who were murdered or missing,” Whitefoot says. “It just wasn’t talked about. Even though I’m considered an elder now, and my sisters are grandmas now, it’s still difficult to talk about this. But seeing what others have experienced gives us all permission to talk. It’s an opportunity to communicate and to ease the pain and anguish and anxiety.

“I have not had resolution and may never get resolution, but at least I’m bringing attention to this issue and doing something about it.”

Whitefoot first came across Ayer through the Little Swan Dancers group Whitefoot had helped create, teaching children the traditional songs and dances of their tribe. Ayer, who had moved to Yakima in 2015, wrote about the dancers, and then a while later, wrote about Whitefoot as one of 52 women who’d been highlighted for their work in the community. Those contacts helped build trust between the two women.

As a general-assignment reporter, Ayer writes stories about the news of the day — whether that’s the pandemic, healthcare, weather, crime or local events. One day in 2018 it was a local state legislator’s bill to start tracking missing and slain Indigenous women. As Ayer began researching, she came across story after story in the paper’s archives about these women.

Unable to find a reliable data set, Ayer began compiling her own list with stacks of stories, obituaries and photos. Along with her 30 years of reporting experience, Ayer had a master’s degree in history and had always wanted to be a historian, so she began digging even further back.

The paper published her first big story on the topic later that year, including the history of a young Yakama woman and her two children who had been killed by white miners passing through on their way to gold fields up north, only a few months after 14 tribes had signed a treaty with the U.S. to create the Yakama Nation and reservation. The crime contributed to the start of the Yakima War of 1855-1858. Ayer had gone with a Yakama historian to the area of the valley where it happened. It moved her.

“I thought, we have to tell that story about her, this case from 1855, and bring it to the present to show how it connects,” Ayer recalls. “It’s a crisis that’s generations in the making.”

She was shocked that most people she came across in town, many of whom had lived there their whole lives, knew nothing about the incident. Her article touched a nerve, and more community members began to tell her of their anguish over the deaths or mysterious disappearances of beloved sisters, mothers, daughters, aunts, nieces and cousins.

“Tammy just kept coming across these stories, and they were impossible to ignore,” says Joanna Markell, the newspaper’s city editor. “We all want justice for the families that have had to go through this. We all want to make sure their loved ones are honored the way they should be. And what that means is not forgetting them.”

Markell knew she needed to give Ayer more time to investigate, but it was a struggle to balance that with the daily grind of reporting amid the looming threat of even more newsroom cuts. So she says it was “a no-brainer” to propose the project when the newspaper was chosen to be part of Microsoft’s journalism initiative.

The team longed for a way to compile everything they were finding from past and current reporting into one digital repository that would allow the information to be preserved and built upon, helping their own reporting and law-enforcement’s investigations while helping readers visually grasp what was going on. The interactive map they came up with pinpoints the approximate location of each killing or disappearance the newspaper is aware of so far. An animated timeline shows when each happened. And graphics give an idea of the diverse geographical setting with its snow-capped mountains, evergreen forests, shrub-steppe grasslands, rivers, creeks and floodplains – especially helpful since some of the 1.4 million-acre reservation is closed to anyone but Yakama tribal members.

“When people see it, it’s one of those visceral things,” says Jason Lilly, the Herald-Republic’s digital strategy editor. “You can immediately understand the scale of the tragedy we’re looking at.”

The work has been painstaking and time-consuming.

“Tammy just handed me a batch of articles from 1993,” Lilly says. “She’s having to do a lot of this from microfilm and archives. I’m amazed by her and the staggering effort she puts into this.”

The Power BI data visualization software is “spawning whole other stories” as well, Lilly says. “Having access to this powerful tool is going to make a big difference, especially in smaller markets like this, because a lot of things going on here get overlooked and don’t get reported, and a lot of people don’t understand the scale of things. We’ve got crime statistics, education statistics and more. There’s a whole other dimension we can start working in.”

News outlets in Yakima are part of Microsoft’s pilot program as well as in Fresno, California; Jackson, Mississippi; the cross-border region of El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico; and the Appleton and Green Bay region in Wisconsin. The news organizations retain complete editorial control.

“Local news is the heartbeat of the community,” says Mary Snapp, the executive sponsor of the effort under Microsoft President Brad Smith. “Without local news, the community doesn’t really know itself.

“And tech is in some ways responsible for the disruption of the previous business model for newspapers, so we know there’s an obligation to help change that dynamic,” Snapp says. “We’re seeing collaboration in ways we’ve never seen before as people realize how drastic the situation is for newspapers.”

In addition to Microsoft’s backing, the Yakima Valley Community Foundation last year put together a Yakima Free Press campaign and advisory group made up of community members to raise awareness and funds to create a sustainable news ecosystem in English and Spanish.

“If we don’t have a way to bring this to light, how can we ever hope this will be resolved?” says Sharon Miracle, the foundation’s president and CEO, who first learned about three years ago that there was a disproportionate number of missing and killed women in the region compared to the rest of the state. “So that’s why we stepped in and said we’re going to try our very best to save our local journalism.”

News reporting is an essential service to a community, says Joaquin Alvarado, a former journalism executive who now consults with news organizations and is an adviser for Microsoft’s Preserving Journalism initiative. Vast news deserts are spreading across the country as newspapers go out of business, leaving entire regions without watchdog reporting or accountability for governments.

“The fact of the matter is that no one else is doing this work,” Alvarado says. “In this case, it doesn’t mean the community isn’t focused, and families and law enforcement aren’t committed, but if not for the Yakima Herald-Republic and The Vanished as a project, there would be treacherous silence in the larger community and in the state on this issue.”

The efforts in Yakima are getting noticed elsewhere by journalists and students keen to do similar work in their areas, building databases of victims and telling their stories with the help of data visualization.

“I’m thankful we have all this technology now to share this issue with as many people as possible in the right way,” Ayer says. “The violence that native women suffer should be of concern to the entire community. We’re all living here, together, and it can’t not affect us. We all have a responsibility to make our community safe. It matters.”

Top photo: Patsy Whitefoot stands near the spot where her sister’s belongings were found, on the Yakama Reservation above Medicine Valley in Washington. Daisy Mae Heath went missing in 1987. (Photo by Dan DeLong)