Nicéa Quintino Amauro always knew who she was.

She was born in Campinas, the last city in Brazil to prohibit slavery in 1888. She grew up in a Black neighbourhood, with a Black family. And a lot of her childhood was spent in endless meetings organized by the Unified Black Movement, the most notable Black civil-rights organization in Brazil, which her parents helped to found to fight against centuries-old racism in the country. She knew she was Black.

But in the late 1980s, when Amauro was around 13 years old, she was told at school that Brazilians were not Black. They were not white, either. Nor any other race. They were considered to be mestiços, or pardos, terms rooted in colonial caste distinctions that signify a tapestry of European, African and Indigenous backgrounds. And as one single mixed people, they were all equal to each other.

The idea felt odd. Wrong, even. “To me, it seemed quite strange,” says Amauro, now a chemist at the Federal University of Ubêrlandia in Minas Gerais and a member of the Brazilian Association of Black Researchers. “How can everyone be equal if racism exists? It doesn’t make sense.”

Amauro’s concerns echo across Latin America, where generations of people have been taught that they are the result of a long history of mixture between different ancestors who all came, or were forced, to live in the region.

In Mexico, for example, most people also think of themselves as mestizos, a term that emerged during the colonial period to explain the blend of ethnicities — especially between Indigenous peoples and the Spanish colonizers. The process of fusion, referred to as mestizaje, has been so intense that a lot of Mexicans say it no longer makes sense to talk about race or racism. The idea of a post-racial society drew important support from early genetic research in the twentieth century and modern human genomic studies, which show that most humans come from a mix of different ancestries. This unifying vision took hold across Latin America, shaping public policies and conceptions about race.

But like all other race-based labels, the mestizo is a social construct, not a well-defined scientific category of people who share similar genetic characteristics. And many researchers have started to challenge the mestizo ideology, which they see as a source of pain for many people — and an obfuscating, sometimes troubling, influence in science.

“The mestizo is everything and nothing. It’s not very descriptive,” says Ernesto Schwartz-Marín, a Mexican anthropologist who probes the relations between genomics research and ideas of race at the University of Exeter, UK. “Why do we look at these categories, born out of the arbitrary nature of the colonial conquest, as biologically significant?”

The mestizo narrative suggests the absence of racism — even when there is ample evidence that skin colour is a powerful determinant of wealth and education levels across Latin America.

And the concept of mestizaje in effect suppressed the visibility and recognition of Indigenous and Black people in the region, while sometimes elevating European ancestry. The concept is another harmful vestige of colonial rule, says Jumko Ogata, who is pursuing a degree in Latin American studies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City. She is also an anti-racism educator and identifies as an Afro-Japanese Mexican. “It has romanticized and misrepresented many histories of dispossession, extraction, violence and colonization,” she says. “It was, and it still is, a profoundly violent thing.”

Her thoughts are part of a broader discussion that’s going on in Latin American society — and in the research community. Critics say that the mestizo myth has had a troubling influence in science. The way the mestizo label has been used in many genetic studies has misrepresented or ignored the histories of people with Indigenous or African ancestries, according to some researchers and activists. What’s more, they argue that this and other categories used in human genetics carry outdated or even racist perspectives.

Some call for banishing the mestizo label in human genetics and adopting much more specific terms not connected with colonial concepts. Others say that the mestizo idea is not as problematic as critics argue.

One thing is clear, says Vivette García Deister, an ethnographer of science at UNAM, who has studied how mestizo ideology has influenced genetic studies in Mexico. “There’s no easy solution.”

Birth of an idea

The idea of mestizaje has come full circle from its origins. In the early 1900s, politicians across Latin America began to realize that this concept could be an effective tool for forging a national identity. At the time, ‘scientifically’ backed racism was prominent in the United States, where pseudoscientific eugenics theory was used to justify stripping people of their rights; this included the forced sterilization of thousands of African American, Native American and Puerto Rican people — which continued into the 1970s. Proponents of eugenics believed that mixing of races could result in ‘degeneration’ and ‘decay’. And they pointed to events south of the border to support their ideas.

The political turmoil that plagued post-independence Latin America was often attributed to the widespread mixing that had occurred since colonial times, and US politicians saw it as a opportunity to intervene, says Juliet Hooker, a Nicaraguan political scientist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. “The idea was that, due to their racial heterogeneity, Latin American peoples were prone to chaos,” she adds. “They couldn’t really govern themselves, so they needed US intervention.”

But some Latin American intellectuals pushed back with the idea that racial mixing was in fact positive. And they formulated theories that encouraged Latin Americans to take up the mestizo identity, which they said combined the best features of each group. Their message was one of social cohesion, which many of these countries used to resist US domination and bring people together under a nationalistic sentiment.

“The mestizo myth was Latin America’s project to put an end to the idea that everything hybrid, everything mixed, was inferior,” says Schwartz-Marín. “It was born as a response to the racist purism of that time.”

This mixed-race ideology has prevailed since the 1920s and 1930s, although not without its harmful aspects. The blend of ethnicities was seen by privileged members of society as a way of ‘whitening’ the nation in the long run. And it disseminated the belief that the scourge of racism could not exist where the boundaries of human differences had been blurred so much.

“Historically, these ideas serve to deny the presence of Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants. To say that they no longer exist, that they have been absorbed by the process of mestizaje,” says Hooker, who experienced this as a girl when her family moved from the Afro-Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, where she grew up, to its mostly mestizo capital. The people there rarely identified as Black, even the ones who looked like her, and repeatedly asked why she identified that way. In 2017, Hooker explored the origins and history of the mestizo myth in her book Theorizing Race in the Americas.

In the 1960s, the United Nations cultural organization UNESCO recognized that there is no genetic evidence for the existence of human races. Still, scientists were interested in studying race mixture, sometimes in ways that supported racist ideas at the time. And Latin America was seen as the perfect real-world laboratory in which to do so.

Brazilian geneticists were particularly productive in the field, and published a large number of papers that tried to explain the ‘trihybrid’ origin of Brazilians with Black, white and Indigenous ancestries; and researchers hunted for ‘racial markers’ to calculate degrees of race mixture.

In Mexico, physician-turned-geneticist Rubén Lisker used genetic markers to map enzyme deficiencies and abnormal haemoglobins, the body’s oxygen-carrying proteins, in what he called “the Indians, the descendants of the Spanish and their mix”. His approach followed the dominant ideology in Mexico, which emphasized mixture between Indigenous people and Europeans, and largely ignored contributions from people of African heritage — although his results did suggest that in certain parts of the country, between 5% and 50% of the genetic variation found in Indigenous populations was also found in African populations1. (During the colonial slave trade, millions of people from Africa were enslaved and taken to Latin America against their will.)

It took many years for Mexico to acknowledge the African connection. In 2015, after a long struggle for recognition, more than 1 million Afro-Mexicans were allowed to identify as such in the national census, which had previously not recognized them. By 2020, the number had increased to 2.5 million people, or 2% of the country’s population.

Mestizo genomics

Until May 2007, Luiz Antônio Feliciano Marcondes never thought his identity would be dissected all across Brazil. But that month, media coverage exploded around his genetic ancestry. As one of the country’s leading samba singers and composers, his Blackness had never been called into question. People needed only to see his stage name, Neguinho da Beija-Flor; ‘neguinho’ refers to his dark complexion and to Brazilians can mean an expression of affection, racism or both.

After examining 40 regions in Marcondes’s genome, a team of researchers led by human geneticist Sérgio Pena at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Belo Horizonte, concluded that Marcondes had a predominantly European ancestry, at 67%. The result came as a surprise. “European, me?” he said in an interview. “I go by the colour of my skin.”

The ancestry test was part of a project commissioned by the broadcaster BBC Brazil to reveal the genetic profiles of nine Black celebrities, which showed many of them to have a mixture of different ancestries. These findings belong to a larger body of research that, since the 1990s, has strongly portrayed Brazil as a diverse nation that is also raceless, where everyone is so mixed that it is now impossible to differentiate people genetically into different groups or populations. But the idea of a raceless society conflicts with the lived experiences of many Brazilians, particularly those who don’t identify as white.

The thinking about racial mixing has progressed in different ways across Latin America. In Colombia, although the dominant view casts the country as one mixed nation, there is a strong tendency to divide it into several regions, each one with various types and degrees of admixture. In the Antioquia region, where Spanish colonizers established their first settlements, some people push an almost mythological narrative that exalts their European, white origins, says María Fernanda Olarte-Sierra, a Colombian ethnographer of science and technology at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

So when a paper in 2006 revealed that the ancestry of Antioquians is between 70% and 80% European2, the highest in the country, many people welcomed the findings that essentially reinforced the view of themselves as mostly non-Indigenous and non-Black, Olarte-Sierra says. But she notes that scientists only sampled people from the highlands, who mostly identify as mestizos, and left out Afro-Colombian communities living in Antioquia’s coastal area and river valley. “I thought it was a self-fulfilling prophecy,” says Olarte-Sierra. “It had consequences that went unquestioned.”

Another prophecy was self-fulfilled in 2009 when Mexico’s National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN) revealed the results3 of the government-led Mexican Genome Diversity Project. After a four-year effort to collect and analyse blood samples from people living across the country, scientists showed that most of the Mexican population derived from a mixture of Indigenous and European people, the two groups typically seen as contributing almost entirely to the mestizo majority. “This confirmed, on a molecular level, which were the ancestral populations of most Mexicans,” says Gerardo Jiménez Sánchez, a medical geneticist who oversaw the project and was the founder and first director of INMEGEN.

The findings were a major event in Mexico, particularly because multi-ethnic populations had not been included in any of the global efforts to map genetic variation between people, such as the HapMap project, which aimed to capture common variations in the human genome. Jiménez Sánchez announced the results during a state ceremony at the presidential residence and presented them as ‘the book of life’ of Mexicans.

The event left some researchers feeling uncomfortable. “I found problematic that the mestizo ideology was not being questioned,” says García Deister. Although the project set out to measure diversity in Mexico, the study initially included a limited sample of 300 people labelled as mestizos and compared them with 30 people identified as Zapotecs, who represented Indigenous ancestry. Geneticists also sampled individuals from other Indigenous groups, but many were ultimately considered to have significant genetic admixture and they were excluded as ‘genomic noise’, says García Deister, who interviewed several of INMEGEN’s researchers. “Once again, Indigenous populations were somewhat at the service of the nation,” she says, “because we needed them to tell us something about mestizos.”

INMEGEN’s project had a strong focus on genomic medicine, and Jiménez Sánchez says it provided huge amounts of data that have since helped geneticists to understand how Mexican mestizos respond to pharmaceutical drugs and which gene variants, many of them linked to Indigenous ancestry, are related to complex conditions such as diabetes or high blood pressure. “Studying that combination of genes with different ancestries can establish risks for diseases — or, better still, the possibility of protecting you from them,” says immunogeneticist Julio Granados Arriola at the Salvador Zubirán National Institute of Health Sciences and Nutrition in Mexico City.

But some worry about this attempt to find risk alleles and link them to certain populations of Indigenous ancestry. This essentially blames Indigenous people for health problems seen in Mexican mestizos, says Jocelyn Cheé Santiago, a Zapotec genomic scientist who is studying the philosophy of science at UNAM. “You stigmatize a whole population.”

Those studies might be seen as supporting the idea that disorders such as diabetes and obesity, which affect millions of Mexicans, are partly due to diets or lifestyle, but mostly to genes inherited from their Indigenous ancestors, says Peter Wade, a social anthropologist at the University of Manchester, UK, who has studied race issues and mestizo genomics across Latin America. “It’s kind of [implying] these health problems are somehow the fault of the Indigenous people or Indigenous ancestry.”

Jiménez Sánchez did not respond to specific questions about these criticisms. “It is always very useful to know other points of view,” he said. “But those concerns that were genuine at the beginning have not occurred. They didn’t come true. I don’t see them.”

The medical focus on mestizo genetics might also create false hopes. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Granados Arriola publicly affirmed that the mosaic-like genome of Mexicans would act as a barrier to slow the spread of the virus. The hypothesis, he explained in May 2020, relies on the presence of protective variants inherited by the Indigenous ancestors who survived the plagues brought by European settlers. He continued to support that hypothesis this year. “What I expect is that most Mexicans with Indigenous genes, regardless of other factors, will have greater protection” against severe disease, Granados Arriola told Nature in June.

So far, little evidence exists that specific genetic ancestries account for lower or higher rates of coronavirus infections4. Today, Mexico has one of the world’s highest COVID-related death tolls, with a total of more than 295,000 deaths.

Back in Brazil, Marcondes’s ancestry test indicating a strong European component figured in fierce public debates about who qualifies as Black. And previous genetic data produced by Pena and his colleagues took centre stage in the conversation.

Since the 1980s, as Pena began his research on paternity tests, he was struck by the “tremendous” genetic diversity he saw in the samples he examined. For more than two decades, Pena’s studies5 have repeatedly shown that the genome of each Brazilian is a unique collage assembled from three ancestral groups: European, Indigenous and African populations. In colonial times, this was typically the outcome of European men raping women of Indigenous and African heritage.

Pena’s research has also demonstrated that admixture has slowly but surely uncoupled genetic ancestry from physical traits such as skin pigmentation, a finding that has been confirmed by other research groups6. This means that one cannot safely predict another person’s skin colour from their genetic ancestry, or vice versa.

The evidence convinced Pena that “there are no human races and that racism is stupid”. He adds that his work has been guided by an anti-racist agenda. “My idea is that if Brazilians realize how much they owe to their Amerindian and African ancestry, we should be able to abolish racism in Brazil.”

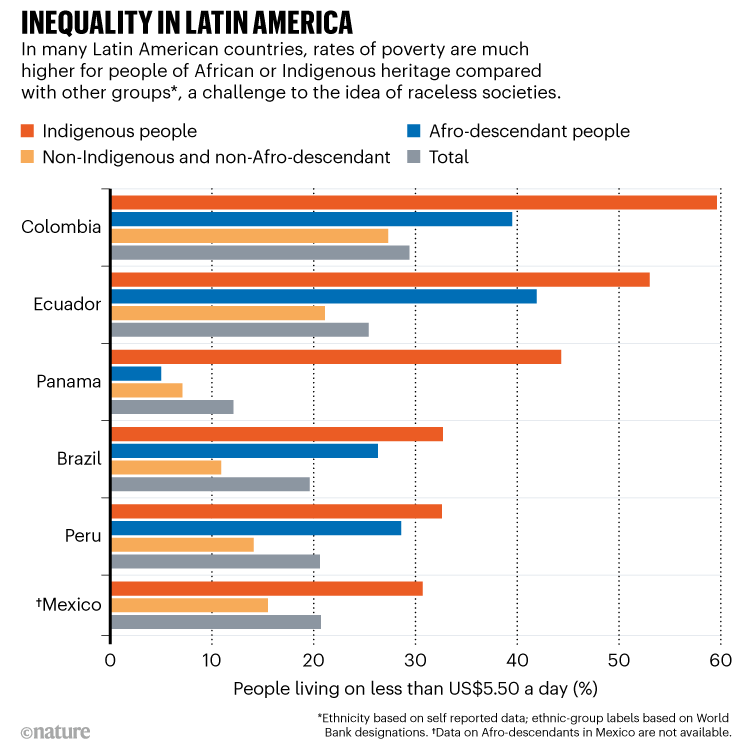

Other people latched onto his results, particularly those supporting the biological non-existence of race and those showing generalized mixture among Brazilians. In 2009, these studies were used by the centrist political party Democratas to support a petition to the country’s supreme court asking it to revoke racial quotas for access to public universities. Pena’s genetic data also inspired an anti-quota manifesto. The document, signed by 113 geneticists, social scientists, politicians, lawyers and citizens, argued that such policies represented a model imported from the United States, and were inappropriate for a country as mixed as Brazil. This was despite evidence that Afro-descendant people (that is, those with African heritage) generally face more inequalities in health care, education, employment, income and housing in Brazil and other Latin American countries (see ‘Inequality in Latin America’).

Pena himself signed the manifesto and participated in the supreme court hearings, giving evidence on the non-existence of race at the genetic level. But he defends his position as neutral. “Our genomics work on Brazilians is primarily descriptive and, as such, it is essential to understand who we are.”

In 2012, the court finally declared that genetics was irrelevant when it came to affirmative-action laws, but some researchers think the legacy of this event has been hurtful. “Our issues are not genetic,” protests Amauro, the Brazilian chemist. “To be discriminated against in Brazil, it’s enough for you to have a certain skin coloration, a certain hair texture, a certain jaw, nose, mouth.”

A path forward

As genomic science in Latin America grappled with the legacy of mestizo ideology, some scholars decided to dissect that relationship and chart a path forward. “We were interested in how science was becoming involved with, challenging, reinforcing, changing ideas about the nation and ideas about race mixture,” says Wade.

In 2010, he teamed up with 13 collaborators in Brazil, Mexico and Colombia to launch a project that explored how concepts of race have influenced genomic research and vice versa, sometimes in problematic ways. The researchers spent more than two years interviewing and shadowing scientists in their laboratories, scrutinizing the methods and language they used and investigating how the results were disseminated. Their findings, compiled in a 2014 book called Mestizo Genomics, speak to continued concerns.

When scientists in the latter half of the twentieth century abandoned the racial categories used by their predecessors, they did so because the data showed that those artificial boundaries simply do not exist. Race, they concluded, has no biological foundation and does not come near to representing the convoluted history of our species. Instead, genetics used a wide range of genetic markers and statistical methods to more accurately reflect the differences and similarities archived in our genes, and found that, in many cases, the resulting patterns broadly coincided with geography — giving rise to clusters that described African, European or Asian ancestries (the term Amerindian, also widely used, was originally created as a linguistic category).

But according to Wade and his team, these ancestry labels still evoke arbitrary, race-like ideas and categories that were invented in colonial times. The label of mestizo, mentioned countless times by geneticists in the papers they write, also inadvertently resurrects the concept of race that science has worked so hard to lay to rest, Wade says.

“If you’re talking about mestizos, you definitely are talking about race,” says Wade, adding that the mestizo, as a concept, has always symbolized a mixture between white colonizers, Indigenous communities and sometimes enslaved Africans and their descendants. “Every time you talk about mestizos, you’re automatically invoking the existence of those categories.”

Ethnographers and anthropologists also take issue with how geneticists have tended to use Indigenous or Afro-Latino populations, considered to be essentially homogeneous, as outside groups or reference points against which to compare mestizo samples. Sometimes this is done to understand how mixing occurred. But critics allege that the practice replicates the nationalistic divide that has defined these groups as separate — and they say that genetic studies seem to incorrectly assume that genetic admixture has not occurred in non-mestizo populations.

“That drove me crazy,” says Schwartz-Marín. “Who is mestizo? Well, it depends on who you consider more or less mixed.”

Change, however, is not a quick process. “Sometimes it’s difficult to get rid of the term overnight,” says Andrés Moreno Estrada, a population geneticist at the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity in Irapuato, Mexico. In 2014, he and his colleagues set out to map the genetic blueprint of Mexicans, only to find a striking amount of diversity in the country — with some Indigenous groups in Mexico being as different from each other as Europeans are from East Asians7. Their results also suggested something else: mestizos and Indigenous groups are pretty much the same at the DNA level.

“If you take a mestizo and an Indigenous person from the same region, genetically they are indistinguishable,” Moreno Estrada says. “This dichotomy has no biological basis.”

Mestizo is not the only category that has gone relatively unexamined in human genetics. An analysis of biomedical papers since 2010 found that nearly 5,000 of them used Caucasian — an eighteenth-century term deeply rooted in racism and genetically meaningless — to describe certain populations.

“The way that we name the [genetic] clusters that we see affects people’s understanding of race,” says Jennifer Raff, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. In June she co-authored a preprint8 about how some widely used categories, such as Caucasian, carry scientifically misleading or even racist perspectives. The goal, says Raff, is to stimulate a much-needed conversation about the language of genetics. “Let’s really dig down — let’s really talk about what we’re doing and how we’re doing it,” she says, “and what that means.”

Although the category mestizo is still in use, some geneticists have chosen to replace it with different terms, such as ‘admixed population’, ‘population of mixed origin’ or ‘cosmopolitan population’. Moreno Estrada says this at least strips away the historical and political baggage and the social implications of mestizaje. But others have come up with entirely new taxonomies.

When Colombian geneticist and statistician William Usaquén travelled to the Colombian La Guajira desert, at the northernmost tip of South America, to describe the genetic composition of the people there, he soon realized that the standard, clear-cut categories of genetic ancestry would not be good enough. The region, he learnt, is the home of the Indigenous Wayúu people, but other communities who do not consider themselves Indigenous, such as the guajiros, have also lived there for generations. What’s more, since the 1800s, the area has been a smuggling route, which attracted migrants from other parts of Colombia who settled. Usaquén found that some people had multiple ancestries and others belonged to families that had always identified as either Wayúu or guajiro.

“By this point, the categories of Amerindian or mestizo didn’t fit anywhere,” says Usaquén, who works at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá. He and his team decided to try something new. They came up with a system of seven different categories that accurately reflected the genealogy, history and demography of the population, and were able to determine how each of them genetically interacted with each other9. “There’s no standard category you can use,” adds Usaquén, who found that the Wayuú are a highly admixed group, but still distinct from other people. When thinking about which category to use, he says, “the big conclusion for us is that every time you study a population, you have to create them”.

That’s much easier said than done. Even if geneticists come together to rethink the language they use, “Then what?” says Schwartz-Marín. “Every new category we generate will have its own implications.”

In Latin America, the myth of mestizaje maintains a foothold in different aspects of modern society, including science. And some researchers think it could be time to abandon the idea — particularly those who do not see themselves as fitting into the mestizo narrative.

Amauro is one. She resents the message that all Brazilians constitute one diverse, yet uniform, mixture. “When I put myself in this group where everyone is the same, my characteristics are lost,” she says. “I can be anyone else. And when I am anyone, I am not me.”