From Brazil to the Philippines, secretive governments across the world are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic by covering up data and bypassing public procurement rules, undermining trust in health systems, fuelling anti-vaxxers and putting immunisation campaigns at risk.

Clandestine contracts for medical goods and services have become the norm in many countries, while data on COVID-19 cases and deaths has been manipulated and underreported.

Authorities and heads of states have used the pandemic as an opportunity to gut public bodies dedicated to openness and communication, with the worst offenders forming a rogues’ gallery of coronavirus offenders.

In the global South, the repercussions for already struggling health and governance systems could be catastrophic.

Corruption outbreak

This is a tale of two pandemics, says Jonathan Cushing, who leads on global health at the anti-corruption non-profit Transparency International.

“You have COVID-19 and then what we’ve seen over the past year is this lack of transparency—the utilization of direct procurement legislation because of the emergency needs at the time,” Cushing tells SciDev.Net.

“We’ve seen repeated cases of corruption, and that is the second pandemic in many ways.”

Malpractice, says Cushing, has been reported “around the world, in the Philippines, in Uganda, we’ve seen cases raised in Kenya, Latin America as well”.

“As the pandemic has progressed, we’ve seen the shift from the rush to buy [personal protective equipment] and ventilators … to the procurement of vaccines,” says Cushing.

“What we’re seeing now is a complete lack of transparency.”

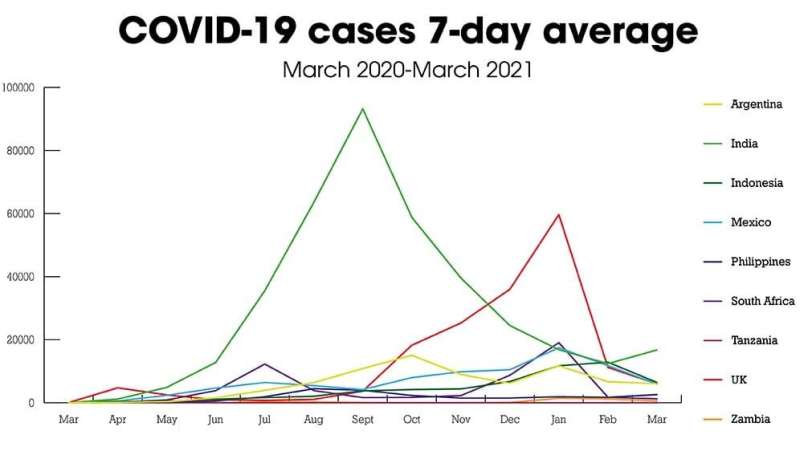

Tanzanian President John Magufuli may have been a victim of his own refusal to acknowledge the presence and seriousness of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

In June, Magufuli declared that “the corona disease has been eliminated by God”, leaving Tanzania “coronavirus-free”. The government stopped publishing data on case numbers, while disease surveillance and advocacy wound down.

Magufuli’s death—officially from heart problems, but widely believed to be connected with COVID-19—was announced on 17 March.

Residents of Tanzania’s largest city, Dar es Salaam, told SciDev.Net it remained to be seen whether Tanzania’s government would reverse Magufuli’s increasingly authoritarian policies. But new president Samia Suluhu Hassan has already marked a departure from her predecessor, pledging to form a scientific advisory committee on COVID-19.

Epidemiologists say statistics will be central to any new evidence-driven response. For now, the data deficit remains as people continue to fall ill.

“What’s lacking now in Tanzania is an enabling environment that allows scientific enquiries on such things as pandemics,” says Frank Minja, a Tanzanian doctor and associate professor of neuroradiology at the Yale School of Medicine’s radiology and biomedical imaging department, in the US.

“Of course, science doesn’t work in isolation, it needs economic and political decisions. But science is a tool that should be used to solve our problems.”

Data in the dark

For the countries that are publishing statistics, many of these have been massaged to reveal a rosier version of reality.

Data manipulation is a key marker of COVID-19 corruption, according to Transparency International. This can have devastating consequences, such as resources misallocation, spikes in case rates as citizens are encouraged to carry on as normal, and increased mistrust in governments when reality does not match with the official version of events.

Multiple studies, including those based on rates of population with COVID-19 antibodies, have suggested that SARS-CoV-2 is more prevalent in many countries than official statistics reveal.

One such study, carried out in Zambia and published in the BMJ, observed “a surprisingly high prevalence of COVID-19 mortality”.

The research team, led by Lawrence Mwananyanda from Right to Care, said: “Contradicting the prevailing narrative that COVID-19 has spared Africa, COVID-19 has had a severe impact in Zambia. How this was missed is largely explained by low testing rates, not by a low prevalence of COVID-19.

“If our data are generalisable to other settings in Africa, the answer to the question, ‘Why did COVID-19 skip Africa?’ is that it didn’t.”

In response, pathologists from the Ministry of Home Affairs and Zambia’s University Teaching Hospital said the conclusions from the Lusaka study were “highly questionable” and could not be extrapolated to all of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Researchers in India found that COVID-19 infections had been grossly underestimated and could be up to 95 times higher than the official numbers. Health and development economist Anup Malani told SciDev.Net that the high seroprevalence—the number of people who tested positive for COVID-19—in the rural areas studied was due to mass migration from the cities to escape lockdown restrictions.

In Brazil, the country’s health ministry removed cumulative COVID-19 data from its website in June as President Jair Bolsonaro declared that the statistics did not “reflect the moment the country is in”.

The supreme court ordered that the data be restored, and the figures now indicate that Brazil is among the worst affected countries in the world, as the government appoints its fourth health minister since the pandemic began.

Attacking the messengers

Those who refuse to toe government lines have faced repercussions, from losing their jobs to legal intimidation and verbal attacks.

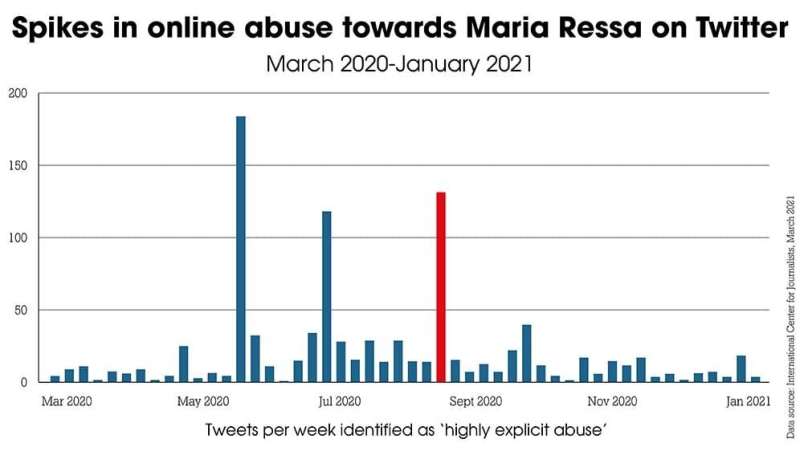

After she criticized Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte and his government over its handling of the COVID-19 crisis, a barrage of online abuse was directed at Maria Ressa, the founder of the Philippines-based news site Rappler.

Ressa is an outspoken Duterte critic, but analysis by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) shows that the second-highest spike in abuse of Ressa correlated to her questioning the official reporting of COVID-19 data.

“Ressa lives at the core of a very 21st century storm,” says the report, led by ICFJ global director of research Julie Posetti. “It is a furore of disinformation and attacks—one in which credible journalists are subjected to online violence with impunity; where facts wither and democracies teeter.”

Posetti says that state threats and digital violence put journalists—and journalism—at risk in the real world. In January, the tenth arrest warrant was issued against Ressa, who is facing multiple libel proceedings, on top of a six-year jail term, which Ressa is appealing.

Anthony Leachon, a leading physician and public health expert in the Philippines, was forced to quit as a special adviser on the COVID-19 taskforce in June after he publicly disagreed with the Duterte administration’s handling of the pandemic, and argued that the taskforce had succumbed to political pressure.

Leachon also criticized the health department, saying its reporting of COVID-19 was unreliable and delayed, and questioned why the government was favoring vaccines from companies with no safety and efficacy data. The Philippines government has approved the Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines for people aged under 65.

Leachon has continued to call on authorities to release real-time data on COVID-19 infections, which he said will allow local officials to quickly respond with appropriate policies.

For speaking independently, Leachon has been ridiculed and mocked by Duterte supporters. The administration’s spokesman, Harry Roque, said that Duterte repeatedly cursed Leachon during a December cabinet meeting on COVID-19.

“This lack of transparency and urgency is the reason why the Philippines is in a mess right now and has fallen behind its peers in the region,” Leachon tells SciDev.Net.

“We are in the longest continuous lockdown in the world. We are still in quarantine yet we are now seeing a surge in cases … [and] we are still in the middle of the debate on what vaccines to procure, how and what are the selection guidelines.”

In March, the Philippines received its first delivery of vaccines from the COVAX facility—the international partnership established to support vaccine access for low- and middle-income countries. Leachon warns that the lack of openness and transparency in the country risks undermining confidence in COVID-19 vaccines.

Captive information

Attacks on Mexico’s independent freedom of information body—the National Institute for Transparency, Access to Information and Protection of Personal Data (INAI)—intensified with the onset of the pandemic.

In 2019, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s first year in office, INAI reported that the administration was legally challenging at least 30 information requests that the institute had approved.

In January, López Obrador announced a proposal to shut down INAI and replace it with a government agency, a move that Human Rights Watch Americas director José Miguel Vivanco called “the perfect recipe for secrecy and abuse”.

“The INAI has played a crucial role in protecting privacy and ensuring the public can access information about government corruption and human rights violations,” Vivanco said.

Janet Oropeza Eng, an accountability and anti-corruption researcher at the civil society organization Fundar, says that INAI has been critical to efforts to monitor federal government agencies over the past 10 years.

“If INAI disappears or becomes dependent on the executive [branch of government], it would be a regression in terms of independence and autonomy. It is not possible to be both judge and party,” Eng tells SciDev.Net.

“The executive could not order itself to open information. For Mexicans, it would be a step backwards in the right to information that was already guaranteed.”

Transparency International’s Mexico branch has made repeated freedom of information requests for pricing transparency, but “gets nowhere”, according to Jonathan Cushing, from the organization’s global health team.

“And it’s not unique to Mexico, it’s Argentina, in Pakistan they’re trying the same thing. It’s a complete shutdown,” he says.

Gag orders

Cryptic references to ‘pneumonia’ became one of the only ways Tanzanians could talk openly about the disease outbreak, after the government passed a regulation prohibiting reporting on COVID-19.

Under the online content regulation, publishing “public information that may cause public havoc and disorder” is banned, including “content with information with regards to the outbreak of a deadly or contagious diseases [sic] in the country or elsewhere without the approval of the respective authorities”.

Breaches could be met with imprisonment for a minimum of 12 months, a fine of at least five million shillings (US$2155), or both.

Adolf Mkono, a resident of Tanzania’s northern Kagera region, which borders Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda and Lake Victoria, says the fear of being charged under the new regulation is stifling information-sharing.

“Since the end of last year, I have witnessed a number of people dying after complaining of difficulty in breathing. This isn’t normal,” says Mkono

“Maybe it is not COVID-19, but the government should come out and explain what’s causing these deaths. We don’t have the freedom or the facts to say if it is COVID-19,” Mkono tells SciDev.Net in an interview conducted in January this year, before the decision by Tanzania’s new President Samia Suluhu Hassan to form a scientific advisory committee on COVID-19. *

Tanzania’s health ministry did not directly respond to these claims when SciDev.Net sought comment. But, the head of communications shared a video of the ministry’s principal secretary, Mabula Mchembe, saying: “It is not true that every patient who complains of breathing difficulties should be believed to have COVID-19. I have visited many hospitals and what I can conclude is that the COVID-19 situation being talked about is based on social media claims that aren’t true.”

Procurement behind closed doors,

COVID-19 vaccine producers have required governments around the world to sign non-disclosure agreements to keep the price per dose a secret.

“Some countries have created special commissions to negotiate the purchase of COVID-19 vaccines,” the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime said in a January policy paper.

“There can be a lack of transparency, and thus a potential risk of corruption in what these agreements entail.”

With emergency procurement procedures and vaccine negotiations hidden from public view, health system corruption can have a speedy—and devastating—knock-on effect for disease containment.

On 27 March, Mexico’s government quietly revised its official COVID-19 statistics, acknowledging that the true death toll may be 60 percent higher than previously reported.

The country went from being praised by the Pan-American Health Organization for its initial response to the pandemic, to being ranked among the worst performing countries in the world as cases and deaths climbed.

In April 2020 the government issued an open-ended decree authorizing the purchase of coronavirus-related goods and services without the need to carry out the public bidding process.

The result, according to the data analysis project COVID Purchases (ComprasCOVID.MX), by human rights NGO PODER and data journalism initiative Serendipia, was that almost 95 percent of Mexico’s procurement contracts in 2020 were direct award contracts—that is, awarded without competition.

This compares with 2019, when about 78 percent of public contracts were direct awards, according to civil society organization Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity.

And concerns have been raised about the suitability of companies awarded tenders, with many lacking experience in the medical fields or linked to previous corruption cases.

“The worrying issue is that all levels of government—not only federal—are abusing the emergency decree to continue with direct awards without any restrictions,” Eduardo Bohórquez, director of Transparency International’s country branch Transparencia Mexicana, told SciDev.Net.

Data gathered by ComprasCOVID.MX shows that government institutions paid wildly different prices for vital personal protective equipment, such as face masks.

While some government departments paid one Mexican peso—about five US cents—per mask, others paid up to 405 pesos—almost US$20.

Bohórquez says that without a sunset clause in the emergency procurement legislation, Mexico’s public funds and institutions are left vulnerable to corruption.

Vaccines for sale

While there are reports of private vaccine holidays to the United Arab Emirates up for grabs, Pakistan is believed to be the first country to have approved the private import and commercial sale of COVID-19 vaccines.

Transparency advocates have urged the government to abandon the proposal, which would allow Sputnik-V vaccines to be sold at a price around 160 percent higher than the global set price of US$10 per dose.

This would “provide a window of corruption”, as it could mean government vaccines end up in private hospitals for commercial sale and price gouging in the public sector, said Nasira Iqbal, former justice of the Lahore High Court and vice-chair of Transparency International Pakistan, in a letter to the Prime Minister.

“The government should not encourage such a policy of favoring a certain section of the society at the cost of transparency,” Iqbal went on to say.

In response, the Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination secretary Aamir Ashraf Khawaja said private vaccine sales were just one element of the government’s COVID-19 response.

“It was a well considered decision of the Federal government to allow private sector to import vaccine as the national vaccination priorities favored the healthcare workers and the elderly, involving some lag in reaching other segments of the society,” Khawaja said in a letter.

“It may be added that the government is fixing the maximum retail price, leaving room for competition and free market dynamics.”

Potential conflicts of interest between authorities and private drug companies leave opportunity for corruption, say analysts.

SciDev.Net contacted the Pakistan government’s Press Information Department for comment, but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

A Pakistan-based economist, who asked not to be named for fear of government or military reprisals, told SciDev.Net that that while there were few confirmed reports of coronavirus corruption in Pakistan, rumors abound in a country known for its systemic and endemic corruption.

“On the policy side, there are rumors of corruption in the purchase of ventilators and in suppressing case and death data in the province of Punjab early on to create an impression that the incidence of the virus was low,” the economist said.

“On the health front, there has been a lot of skepticism on testing for COVID-19. It is again rumored that for travel purposes, private labs were on purpose providing negative results. This was mainly done for international travel. There was no monitoring, either by the press or by NGOs.”

Additionally, analysts say that the US$1.386 billion pledged to Pakistan in April 2020 under the IMF’s Rapid Financing Instrument was yet to be fully disbursed.

Open science, open societies

The first casualty of coronavirus corruption could well be public trust, says Cushing, as skewed statistics and bent procurement processes give vaccine skeptics ammunition that could hamper responses to the pandemic.

“In the current scenario in the pandemic, trust is key. We need to ensure that there is trust in the system,” Cushing said.

“Part of transparency is about stopping the corruption, stopping those individuals making profit illegally and immorally from this.

“But it’s also about letting people understand and participate in decision making. If you know what’s going on and you can understand what decisions are being taken and can help shape that, it makes it much easier to hold governments accountable.”

The consequences for societies could reach beyond the immediate disease threat. Without open data and open science, communities will be left out of important conversations and in the dark, says Cushing.

Health bodies require data to support “rational decision making” when it comes to prioritizing which drugs to buy. “If that’s not there, then at best you could be wasting money, at worst it could be impacting on health outcomes,” said Cushing.

“The connection between governance and healthy societies is exactly that—you want transparent governance systems and the more transparent they are and the more people can engage in them, there is greater trust in that system.

“That should allow that conversation to happen about where the country goes in terms of health, development, socioeconomic priorities.”

Provided by

SciDev.Net

Citation:

COVID-19, lies and statistics: Corruption and the pandemic (2021, April 14)

retrieved 4 February 2022

from https://phys.org/news/2021-04-covid-lies-statistics-corruption-pandemic.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.