Scope and nature of documents

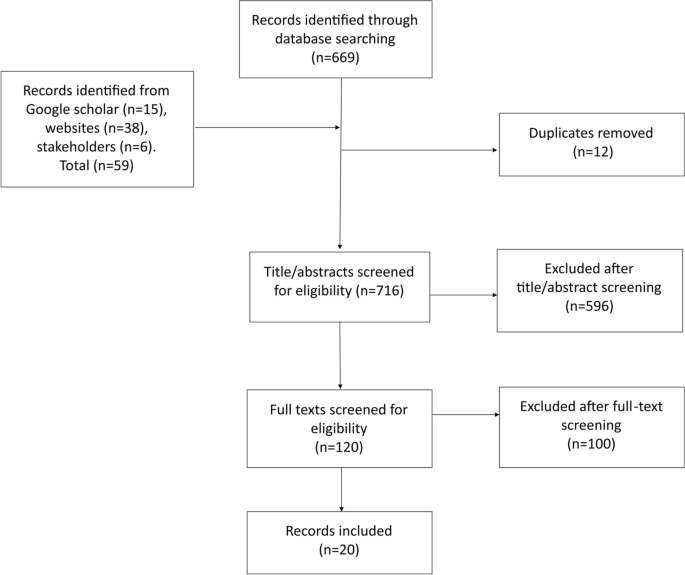

Figure 1 provides the PRISMA flow diagram for 20 sources included of 728 identified through searches. Publication dates began with one source in 1999 (5%) and increased somewhat to a peak of 4 in 2018 (21%), only one in 2019, and none in 2020. Twelve (60%) were journal articles, five (25%) were evaluation or technical reports, two (10%) were WHO updates on EWAR, and one (5%) was a letter to editors.

Countries included were diverse, but predominantly European (i.e. 13 sources), 4 for Italy, 2 for Greece, 1 each for Albania, Germany, Macedonia, and Spain, while 1 included six European countries, and 2 discussed Europe as a region [17,18,19,20,21, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Three from the Africa region discussed camp-based surveillance in Cote d’Ivoire and Sudan, disputed Sudan-Chad borders, and Minawao in Cameroon [36,37,38]. Two from the Asia region discussed surveillance in Bangladesh and the Myanmar-Thailand border [39, 40]. One from the Americas region discussed binational surveillance on the United States (US)-Mexico border [41]. One source was global, including 24 countries [42].

Terminology was also diverse. Only 8 sources used the term ‘refugee’ in describing target populations [30, 33,34,35, 37,38,39,40], 8 used ‘migrant’ as a general term [15, 17, 19,20,21, 32, 41, 42], and 4 combined terms, describing ‘migrants and refugees’, ‘displaced and refugees’, ‘refugees and asylum-seekers’ as the population of interest [18, 28, 29, 36]. Most sources (13; 65%) were descriptive rather than analytical, while 4 conducted health system assessments [19,20,21, 37], 1 used scoping methods [28], 1 used descriptive epidemiological statistics [18], and 1 provided authors’ opinions [30].

Thematic synthesis

We synthesised outcomes under four deductive themes: (i) infectious disease surveillance targeting refugees and migrants; (ii) surveillance methods used; (iii) protocols and policies used; and (iv) reported lessons and limitations described. Table 3 summarises findings by source and theme.

Infectious disease surveillance targeting refugees and migrants

Most sources described migrant disease surveillance in Europe (13; 65%). In initial sources, published in 1999 and 2000, Valenciano et al and Brusin described syndromic disease surveillance systems established in two bordering countries, Albania and Macedonia, in response to the Kosovo crisis [34, 35].

After 2011, specific syndromic surveillance systems were developed in European countries to address increased migrant numbers more quickly. Three examples from Italy described disease surveillance for refugees, primarily from North Africa [15, 32, 33]. One described 6 months of syndromic surveillance in migration centres [32], results of 2 years of syndromic surveillance operated in parallel with existing routine statutory surveillance [15], and multiple other types of surveillance [33]. Riccardo et al. presented surveillance problems during migrant arrivals in the European Union (EU) in a letter to Eurosurveillance journal [30] and described the Common Approach for Refugees (CARE) Syndromic surveillance simulation implemented as a preparedness exercise in Italy [29].

WHO European Regional Office (EURO) assessed health system capacities of several migrant-receiving countries, including in Italy [19], Spain [20], and Greece [21]. The Italy assessment reported that Sicily had a syndromic surveillance system for migrants since 2011, while for the rest of Italy this appeared less active [19]. The Greece assessment suggested regular surveillance activities but no formal system established [21], while migrant disease surveillance was mentioned for Spain with no further details provided [20]. Syndromic surveillance systems were also documented in Greece [18] and Germany [17]. A scoping study, including key informant interviews in six European Union (EU) countries, described surveillance targeting refugees and asylum-seekers [28].

Two Asia region sources described a three-year enhanced hospital-based respiratory virus surveillance programme in a Myanmar refugee camp in Northwest Thailand, to examine pneumonia burden among migrants living on the border [40], and surveillance in Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar Bangladesh (WHO-SEARO, 2018).

Two Africa region sources described Early Warning and Response (EWAR) networks in Darfur, Sudan, and Chad for displaced and refugee populations [36] and surveillance in Liberian refugee transit camps in Cote d’Ivoire [38]. One from Cameroon described activities of a diarrheal disease surveillance in Minawao refugee camp for an evaluation of the system [37].

One Americas region source described collaborative surveillance activities on the USA-Mexico border [41]. One global source briefly describes infectious disease surveillance activities in GeoSentinel clinic sites targeting migrants in 24 countries across six continents [42].

Surveillance methods

Five sources reported surveillance activities supervised or implemented by national public health institutes such as the Institute of Public Health in in Albania, the National Centre for Epidemiology and National Institute of Health in Italy, and Robert Koch Institute in Germany [15, 17, 20, 34, 35]. A few reported assistance or implementation of surveillance systems by international organizations such as WHO in Bangladesh, Darfur, Sudan and Chad, UNHCR and WHO in Macedonia, and US Centres for Disease Control (US-CDC) on the US-Mexico border [34,35,36, 39, 41].

Notifiable disease lists were mentioned for 7 countries, usually consisting of 12–14 diseases and syndromes that were similar across countries [17, 18, 32, 34,35,36]. For example, all lists included acute respiratory infections, meningitis, and diarrhoea. Others included nationally relevant diseases, such as malaria in Greece, Sudan, and Chad, or non-infectious concerns such as psychological and cardiovascular diseases in Albania [18, 34, 36]. Four mentioned the provision of case definitions along with the list [15, 17, 32, 34].

Reporting approaches were passive or active. For passive reporting, as documented in Albania, Macedonia, Italy, Germany, and Cote d’Ivoire transit camps, reports from camps or immigration centres were sent to reporting authorities via online database, fax, email, telephone, radio, or vehicle [15, 17, 34, 35, 38]. Active case finding, as documented in Albania, Cote d’Ivoire transit camps, Cameroon, and Thailand, included door-to-door searches and reviews of medical registers [34, 37, 38, 40]. Reporting speed was either immediate, if fitting immediate notifiable criteria as in Macedonia [35]; daily as in Italian, German, and Greek syndromic surveillance systems [17, 18, 32]; or weekly as in Albania and Cameroon [34, 37].

Coordination meetings between reporting authorities, surveillance teams, reporting sites, and stakeholders were conducted either daily as in Cote D’Ivoire transit camps, weekly as in Macedonia, or monthly as in Germany [17, 35, 38]. One source reported annual binational meetings for border surveillance between US and Mexico authorities [41]. Dissemination of information, as statistical reports or bulletins, was most often weekly and shared during coordination meetings, on national surveillance program websites, via email, or as hard copies [15, 17, 32, 34, 35, 38].

All except four sources described national surveillance systems that tracked migrants. Exceptions were subnational surveillance in Apulia Italy [33] and border areas of Myanmar [40]. Additionally, Waterman et al described binational cross-border surveillance collaboration, with common case definitions established [41]. Finally, McCarthy et al described global GeoSentinel surveillance, mainly through specialised travel and tropical medicine clinics [42].

Surveillance protocols, guidelines, and policies

Eight sources mentioned the existence of surveillance policies, protocols, or guidelines shared with reporting sites [15, 32, 33, 35, 37, 41,42,43]. Instead of a protocol document, Germany’s syndromic surveillance system team developed a toolkit hosted on an institutional website [17]. Some protocols were described as insufficient or poorly defined. For example, interviewees in several EU countries described their guidance on data collection and recording as inadequate [28]. Similarly, prior to the binational surveillance initiative, reporting protocols for US-Mexico land borders were described as poorly defined [41].

Policies related to surveillance were rarely mentioned. Only one source reported a surveillance-related policy change, in which the Italian surveillance system was extended beyond the humanitarian emergency end date to allow reporting centres to apply Italian infectious diseases statutory surveillance [15]. Conversely, Germinario et al. highlighted the EU’s need to enact infectious disease screening regulations for migrant populations [33]. A scoping study of six EU countries mentioned that “legal procedures” usually needed to be surpassed in destination countries, leading to ad-hoc activities [28].

Reported lessons and limitations

Nine sources reported that migrant-specific surveillance systems provided insight into infectious diagnoses and trends among refugees, enabled early detection of potential outbreaks, helped reduce disease transmission in camps, and led to obvious improvements in public health interventions [17, 32, 33, 36,37,38,39,40, 42].

Three reported the additional benefit of closer collaboration between partners or with refugee populations. For example, the Albania source reported that setting up the surveillance system led to close collaboration between surveillance team and health facilities, a task that would have been difficult outside the emergency context [34]. Kouadio et al recounted a reason behind their effective surveillance was cooperation between the surveillance team and refugee population [38]. Waterman et al emphasised cross-border coordination for achieving surveillance goals and common guidelines between US and Mexico [41].

Many sources described lessons on limitations that needed to be addressed. For example, two WHO assessments showed data collection was not systematic, with different databases maintained by different partners, and health-workers in migrant centres noting aspects of the syndromic surveillance system needed to be clarified [19, 21]. Similarly, another mentioned the lack of systematic approaches to surveillance, especially in the EU [30]. One noted that in Greece some diseases were identified through the mandatory notification system operating in parallel to the Points of Care surveillance system for refugees and migrants [18]. Another limitation mentioned was sustainability of surveillance for refugee populations. A study of six EU countries declared sustainability as almost impossible, resulting in ad-hoc systems [28]. Another source from Italy similarly highlighted that ad hoc surveillance cannot be sustained so needs to be corrected “before it can become a routine tool” [15].

Napoli et al mentioned use of paper-based methods for reporting as a logistical limitation, because it was time consuming, led to less timeliness of reporting, and was one of the issues affecting sustainability of the system [15]. They advised shifting to an online reporting platform [15]. Riccardo et al, corroborated this observation that such logistical challenges contributed to underreporting [30].